Posted August 22, 2023.

Danny Heitman’s article, “Francis Bacon, Montaigne’s Rival,” found at https://www.neh.gov/article/francis-bacon-montaignes-rival, disappointingly, uncritically repeats the usual biographical narrative on Bacon, emphasizing its negative aspects. For example, it repeats what is generally said, that Bacon did not believe the Copernican theory was correct. I do not believe one can be so sure about that, judging from my reading of his writings as a whole [see additional note at end of this essay]. Due to the political censorship and religious persecution of the time with its impeding effect on scientific advancement, one had to be careful what one said in print. Heitman also repeats the usual criticism of Bacon that he prosecuted Essex who, it seemed, had been trying to overthrow the government. Yes, Essex had been his friend, but it should be remembered that Bacon could not refuse. He was a lawyer in the Queen’s service and had to do as she commanded him, despite his personal feelings. To get a full and fair story, one must dig a little deeper.

It is true that he wrote to his uncle William Cecil, “I have taken all knowledge to be my province.” Actually, he was quoting a classical source, as he so often did. He was trained in Greek and Latin and had an affinity for the ancient world, as he once wrote to a friend. He was also a linguistic genius who added many new words to the English language which we use every day. Many of these came from Latin.

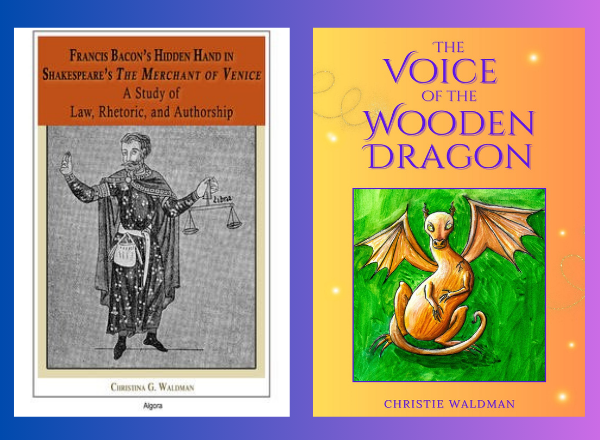

Heitman’s article is dismissive of Bacon’s having written Shakespeare, without much discussion. The reasons given are the usual: that the idea has been “roundly dismissed by serious scholars” and that Bacon’s writing style differed from Shakespeare’s. Short answers: (1) we are entitled to make our own investigation of the facts; we do not have to just trust the experts, and (2) of course a person would use a different style for writing dramatic poetry than he would in writing legal arguments or philosophy.

The article does not mention Bacon’s contributions to the law as a jurist or as a legal and educational reformer; rather, it characterizes him as a “philosopher, statesman, and pioneer of science.” However, it downplays his contributions to “science.” It does not mention that he was also as a historian, the author of The History of the Reign of King Henry the Seventh. It characterizes him as akin to Machiavelli: “sharply incisive but also a little bloodless.” Is that fair? I don’t think so. Much has been written about Bacon’s–and “Shakespeare’s”–familiarity with Machiavelli that is not even touched upon in that quick epithet. It is important to know one’s enemy. Historically, most writers have taken Machiavelli’s The Prince at face value, but the lawyer and legal scholar Alberico Gentilli in Bacon’s own time was convinced it was a satire (see, e.g., L. J. Andrew Villalon, “Machiavelli’s Prince: Political Science or Political Satire? Garrett Mattingly Revisited,” Mediterranean Studies, vol 12 (2003), 73-101, https://www.jstor.org/stable/41166952; Garrett Mattingly, “Machiavelli’s Prince: Political Science or Political Satire?” The American Scholar 27, no 4 (1958), 482-491); see also my review, “Review of Innocent Gentillet [attributed]. Anti-Machiavel: A Discourse Upon the Means of Well Governing [London, 1602; first pub. anon., Geneva, 1576]. Edited by Ryan Murtha, translated by Simon Paterick.” Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2018.Modern Language Review, vol. 115, no. 3 (July, 2020): 682-684).

Heitman’s essay suggests he was unfamiliar with Daniel R. Coquillette’s Francis Bacon (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1992) which claims to be the “first modern book to describe Francis Bacon’s jurisprudence” (book jacket) or Nieves Matthews’ Francis Bacon: The History of a Character Assassination (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996). For, if Heitman had read Matthews, would he have been content to write, “Regardless of the circumstances, the taint on Bacon’s character has endured, and it has compromised his literary standing too,” without noting Matthews’ able 592-page rejoinder? Public opinion can be a dangerous thing when it masquerades as truth. As Matthews wrote, “Readers may be forgiven for succumbing to the deceptions practiced upon them by the trained minds who have placed their scholarship at the service of a preconceive image. The best historians have been taken in ….” (Matthews, p. 433). The truth always has more than one side.

Is the bias which certain authors have created/perpetuated about Bacon justified? What of Bacon’s high reputation during his own lifetime, among those who knew him best? (“That Angel from Paradise,” Matthews, ch 2). What of the rediscovery of Bacon in the 21st century by Benjamin Farrington, Perez-Ramos, Brian Vickers, Graham Rees, and others? (“The Sterile Philosopher,” Matthews, ch 33). Catherine Drinker Bowen, who wrote a biography of Bacon published in 1957, The Temper of a Man, said that, of all the people she had written about, the one she would most like to spend an afternoon with was Francis Bacon (See Catherine Drinker Bowen, “The Search for Francis Bacon,” The Atlantic, January, 1966,https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1966/01/the-search-for-francis-bacon/660070/).

Heitman might have also included in his bibliography collections of Bacon’s Works, notably, Spedding’s 14-volume Works of Francis Bacon and the Oxford Francis Bacon Project. On the topic of Bacon’s essays, he might have mentioned “Castalian Spring”‘s ongoing series of essays on Bacon’s essays, Blogging Bacon, on Medium (2021-2022), https://medium.com/essaying-bacon/latest.

I don’t mean to be unduly harsh in critiquing Heitman’s article. It is just that I do care about this subject. Francis Bacon was a fascinating, many-faceted, and genuinely good person. Brian Vickers, author of many books and articles on Bacon (and on Shakespeare), wrote, “Francis Bacon is exciting!” I agree. He was a genius, a humanitarian with an overarching vision for improving the lot of the human race. We have so much to thank him for. As we sit typing on our computers, let us remember that he invented the bi-literal cipher upon which computer technology is based. Let us not be content with the surface narrative we’ve been taught, but dig deeper and make our own inquiries. For, with Bacon, there is always another level to explore.

Heitman’s article was published in Humanities magazine and at the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) website. The NEH is funding a project, “Six Degrees of Francis Bacon.”

Note (Aug. 28, updated Sept. 9, 2023: I had included the above material at my “Bacon on the Web” page (this website) in April, 2023. On May 1, I emailed a copy to an NEH editor who responded the next day, stating that they valued my comments, their essays were from “seasoned writers with their own points of view” and that their articles were “carefully fact-checked” and “for a general audience.” He offered to discuss the matter further, but I declined. I was satisfied with his response.

Additionally: It is often stated that Bacon had rejected the Copernican theory. Consider, however, whether it might be more accurate to say that he did not think it had yet been sufficiently proven. Bacon’s Advancement of Learning came out in 1605. Galileo in 1610 saw for the first time that moons orbited Jupiter which was a necessary step in the proof of the Copernican theory. Learning had not advanced sufficiently to conclusively prove the matter until Newton proved it in 1687 (“Planetary Motion: The History of an Idea that Launched the Scientific Revolution,” NASA (scrolling down about l/3 on the page) https://www.earthobservatory.nasa.gov/features/OrbitsHistory). Bacon corresponded with Galileo (see Spedding 14:35-36). One might see in the name “Shakespeare” a simple expression of a belief that the “earth moves” (with shake including the meaning of “revolve” and speare as “sphere”), if it were a pseudonym. Certainly Bacon held theories that modern science later disproved, as well as proved. But what he was trying to do was lay a foundation upon which modern science could build, and that required that we build on certainty, not supposition. That is how I read it, anyway. Perhaps at a later date I can revisit this and provide references in Spedding to everything Bacon said about the Copernican theory. It would be like Bacon to reserve judgment until the matter could be satisfactorily proven.

An essay by Sir George Greenwood discusses some of the passages in Bacon’s writings: “The Common Knowledge of Shakespeare and Bacon,” in E. W. Smithson, Baconian Essays, with introduction and two essays by Sir George Greenwood (London: Cecil Palmer, 1922), pp. 161-187, 178-181, 179 fn 87; see also 27, 126, 129 (Smithson mentions Copernicus as well at 126, 178-81).

In Hamlet, the character Polonius said, “Doubt thou the stars are fire, doubt that the sun doth move, doubt truth to be a liar, but never doubt I love” (Hamlet, II, 2, 1212-1214, 1864 Globe ed., www.opensourceshakespeare.org). One possible reading is: doubt a statement I think is true (a truth), doubt a statement I think is false (a lie), doubt that truth lies; but never doubt I love. Doubt a truth, doubt a lie, doubt truth lies, but never doubt I love. At any rate it is ambiguous. If words spoken by a character can be trusted to tell us anything about their author, it might be only that, while he may have an interest in these new scientific theories that he put into his character’s mouth, he is good at going right up to the line of what he can get away without crossing it. Incidentally, the word “doubt” or a form of it appears 257 times in Shakespeare. Bacon wrote, “If we begin with doubts, we will end with certainties. If we begin with certainties, we will end with doubts.”

On the issue of whether Bacon wrote Shakespeare, Greenwood remained–like what I am suggesting for Bacon on the Copernican theory–unpersuaded. It was not that Greenwood did not find the theory that Bacon wrote Shakespeare plausible; he did. However, he was a barrister, a lawyer. He was used to standards of proof. He did not believe the matter had been sufficiently proven. Thus, he considered himself to be an “agnostic” on the matter of Bacon’s authorship of Shakespeare, although, paradoxically, he wrote extensively on Shakespeare’s vast knowledge of the law, for that ought to point to Bacon as the author, in my opinion. (Greenwood, ed., introductory essay, 7-41, 28, 33; “The Common Knowledge of Shakespeare and Bacon,” 161-187, 164; “The Northumberland Manuscript, 187-223, 205; and “Final Note, 223-230, 230, Gutenberg link), in Smithson, Baconian Essays. I am very grateful to “Eric Roberts” for mentioning–in a SirBacon.org forum discussion–the Smithson book.

Essays in Shakespeare and the Law: How the Bard’s Legal Knowledge Affects the Authorship Question, edited by Roger A. Stritmatter (Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship, 2022) discuss Greenwood without, however, mentioning his Baconian essays. even though their book just mentioned includes Greenwood’s essay, Shakespeare’s Law, in full (pp. 41-63; first pub. London: C. Palmer, 1920) and two essays, Mark Andre Alexander’s “Shakespeare’s Knowledge of Law: A Journey through the History of the Argument” (2001) and Tom Regnier, “Could Shakespeare Think Like a Lawyer?” (2003), which discuss Greenwood’s writing on Shakespeare (see 12, 115-116, 118, 120, 130-137, 139-155, 160-161, 167, 168 (Alexander); 193, 196, 197, 211-215, 226 (Regnier).

The Oxfordians like to talk about Greenwood. Greenwood provides support for the theory that Shaxpere was not Shakespeare. He also provides support for the theory that, whoever Shakespeare was, he was well-versed in the law, judging from his plays and poems. However, did Greenwood ever say he thought it was plausible that Shakespeare was Oxford? At this stage in my reading, I do not know. I would like to know. However, it is clear that, in terms of legal accomplishments–if we concede that whoever he was, Shakespeare was someone who knew the law intimately–Bacon was far more qualified than Oxford. But further elaboration on this must wait for another time.