Hi, my name is Christina Waldman. When I was younger, I thought all I needed to be productively happy were a decent typewriter, a sewing machine, and a piano. Now, of course, the typewriter has morphed into a computer, there are space-age sewing machines that Grandma could never have imagined, and the piano is more likely to be an electronic keyboard. Still, there were pluses to the old models. My old Underwood typewriter was free of security risks. Many beautiful old cast-iron sewing machines, like Mom’s treadle or Grandma’s old White Rotary, my first sewing machine, still work after years in storage, unlike modern machines. A piano is a lovely thing to have in a home, but they are so hard to move! I have had to say good-bye to several over the years.

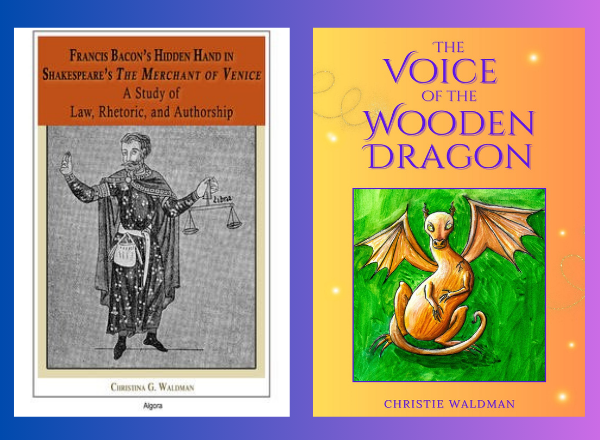

I am the mother of grown children and a grandmother. I love books and learning, art and music. I love beautiful old buildings like libraries and churches. I believe in the value of humanities and arts education. In the past few years, I’ve allowed myself to indulge in a passion for patchwork and quilting. Once you embrace this empty nest thing, it isn’t so bad! It has given me time to do some of the things I always wanted to do, like writing Francis Bacon’s Hidden Hand. And now, my children’s fantasy novel, The Voice of the Wooden Dragon, has been published by NFB Publishing in Buffalo, New York. It is also available from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and other online sellers.

I studied history and law at Southern Illinois University at Carbondale, Illinois. Over the years, I have practiced law from a home office and written for publishers of legal reference books. When, in 1982, I couldn’t decide whether to go to law school or “be a writer” (not realizing one could do both), I wrote to one of my favorite authors, Bernard Malamud, asking his advice. I had just finished reading his book, Dubin’s Lives. His advice for writers: “You must know and love literature and read and think of it endlessly.”

When I was in college, I used to wonder why the world had never produced another Shakespeare. I figured it had something to do with the way we educate children. Francis Bacon had a lot to say about education. He recognized the educational value of the theater, praising the Jesuits particularly in this regard. Maybe there will never be another Shakespeare. Maybe he was not just one person. But don’t we want to be educating the whole person, putting a priority on arts education? Studies show that the benefits go far beyond just fostering creativity, though this world certainly needs creative thinkers to solve its many problems.

For children during the pandemic, my daughter Eliza and I did a story-song project, combining my story, “Slippers for Molly”) with her song, “Pink Bunny Slippers.” https://christinagwaldman.com/slippers-for-molly-a-childrens-story/. See also “Children’s Corner,” this website.

It is hard to imagine Francis Bacon having a public website–he whose invention of the binary cipher led to the development of the first computer. He was a very private person. I wonder what he would think of the idea.

More About Francis Bacon’s Hidden Hand: Abstract

This book explores The Merchant of Venice, by William Shakespeare who has been assumed, on the basis of tradition (which, then, must be subject to critical assessment), to be William Shaxpere (1564‒1616), the actor from Stratford. The book focuses on the character “Bellario,” the old Italian jurist who, when summoned by the Duke to court, to advise him in the matter of Shylock v. Antonio, makes his excuse of illness and recommends that the Duke allow his protegeé “Balthazar” (Portia), to “appear” (make a court appearance) in his place. This book sees the play as a treasure hunt (like the hide-and-seek game ring-o-lario). Bacon was a man interested in how people learn. He was one of the first–as was Shakespeare–to use the word “hint” in its modern meaning of “to suggest, give a clue,” or, perhaps “to cue”). The book explores whether Francis Bacon, the self-described “bell-ringer who calls all the wits together” and inventor of the inductive method, might have written the play. Readers may not be aware that Francis Bacon wrote religious satire, or that he was so witty people scribbled down the things he said at dinner parties, or that he confessed to writing “toys” or “trifles” for his own “recreation.” It has been conceded that Shakespeare’s plays are full of law. However, some of it is not readily apparent, but requires close looking (“curious” or close reading, Bacon might say). sleuthing. Among other topics, this book examines: what Bacon was doing when the play was written (“Tower work,” Spedding called it); play sources such as the Processus Sathanae (a 12-13th century legal satirical law treatise), Bacon’s Maxims of the Law, Meditations Sacrae, and Colors of Good and Evil), the Ordo Bambergensis; law and equity; and Stephan Kuttner’s “a forgotten definition of justice.” It explores the possibility that Bacon, a common-law English lawyer who was a “closet civilian” in Protestant England, preserved valuable knowledge in verse form, like the ancient Roman “scientific” poet Lucretius had done, in order to help ensure its preservation for future generations. What can we learn from an “inquisition” into Shakespeare’s Bellario? There is one thing for certain: things are not what they seem in The Merchant of Venice. There always seems to be another layer to explore.

(last reviewed 11-16-24)

A Renaissance lady indeed. Well done.

Dear Julie, Thank you so much!