This will be a work in progress where I will try to point out and comment on things that have come to my attention (as time permits). As a general observation, I would say you have to do your own fact-checking, even of encyclopedia articles, online. They are not always written by unbiased experts who have a scrupulous regard for factual accuracy, it would seem. Some even seem to treat Francis Bacon as if he were fair game for jokes and humor (like Genius.com, “Popular Francis Bacon Songs”). Categories: Positively Noted, Courses on Bacon, Caveats, and Resources. If a writer or editor gives an opinion, does he support it with reasons and examples?

Positively Noted

Matthew Sharpe, professor at Australian Catholic University, “Francis Bacon’s Essays explore the darker side of human nature. 400 years later, they still instruct and unnerve.” The Conversation, Aug. 5, 2025, https://theconversation.com/francis-bacons-essays-explore-the-darker-side-of-human-nature-400-years-on-they-still-instruct-and-unnerve-259051; “Looking for truth in the Facebook age? Seek out views you aren’t going to ‘like.'” The Conversation. March 12, 2018. https://theconversation.com/looking-for-truth-in-the-facebook-age-seek-out-views-you-arent-going-to-like-91659.

Read the latest digital edition of Baconiana, vol. 2, no. 1 (Nov. 8, 2024), journal of the Francis Bacon Society, at the Francis Bacon Society website. Now published annually.

The Francis Bacon Society has an online bookstore! There readers may purchase the 2024 reprinted Francis Bacon Society Edition of N. B. Cockburn, The Bacon Shakespeare Question: The Baconian Theory Made Sane (1998). At last, this book is back in print! Readers will find other books of interest there as well.

Spearshaker Productions. https://www.spearshakerproductions.com/. Their stated goal is to produce a drama about the life of Sir Francis Bacon.

Watch actor Jono Freeman‘s Bacon-Shakespeare videos at Jono Freeman33, https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCU6OOFE4_Jg3cl7EvOVGyyg.

Kate Cassidy, “The Shakespeare Authorship Question: Unraveling the Mystery: Who wrote the Plays, and Why?” https://the-power-paradox.shorthandstories.com/the-shakespeare-authorship-question-unravelling-the-mystery/index.html. Kate is the author of The Secret Work of an Age, available from https://www.the-secret-work.com/author.html/ or Amazon.

“Francis Bacon,” Theosophy Wiki, last updated July 3, 2025, https://theosophy.wiki/en/Francis_Bacon.

Key Baconian websites: SirBacon.org (“Francis Bacon’s New Advancement of Learning”), https://sirbacon.org/sirbacon-org; The Francis Bacon Research Trust (Peter Dawkins, founder and principal), https://www.fbrt.org.uk/ (essays listed under “Resources”), the Francis Bacon Society website, https://francisbaconsociety.co.uk/ The articles and books of independent researcher A Phoenix are available at https://aphoenix1.academia.edu/ and from A Phoenix’s contributor page at SirBacon.org.

Quotations pages: A Phoenix, Youtube, collected at SirBacon.org (Oct. and Nov., 2022, https://sirbacon.org/quotes-about-francis-bacon/; “Sir Francis Bacon,” TODAYINSCI (Today in Science History), https://todayinsci.com/B/Bacon_Francis/BaconFrancis-Quotations.htm (however, as to Robert G. Ingersoll’s 1891 lecture, “Lord Bacon Did Not Write Shakespeare’s Works,” which the site mentions, Ingersoll’s view of Bacon as a scheming politician, etc., has been ably countered by Nieves Matthews in her book, Francis Bacon: The History of a Character Assassination [New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996]).

Karen Attar, librarian, “Books and buildings, if not big data, the Durning-Lawrence Library,” Talking Humanities, Feb. 4, 2022, https://talkinghumanities.blogs.sas.ac.uk/2022/02/04/books-and-buildings-if-not-big-data-the-durning-lawrence-library/.

“Castalian Spring,” “Blogging Bacon–Essaying Bacon, Initiative Essays on Bacon’s Essays,” on Medium.com. Why blog Bacon’s Essays, or Counsels, Civil and Moral. Says Castalian Spring: “Bacon’s essays are everywhere rightly admired as a classic of renaissance literature but rarely critically examined as works of condensed philosophical counsel. These little blogs aim to get beyond the beauty of the prose, to provide the first full philosophical survey of Bacon’s classic of “cultura animi” (the cultivation of the self”), as well as their civil and moral wisdom, breaking down the ornate language and applying the ideas to contemporary affairs.” https://medium.com/essaying-bacon.

SirBacon.org

Sirbacon.org celebrated twenty five years in October, 2022. Check “What’s New” for the latest additions. The site is a virtual library; there is so much information there. I relied upon it a lot when I was writing Francis Bacon’s Hidden Hand. Here are links to pages I found helpful:

“Bacon versus Shakespeare: A Judicial Decision that Francis Bacon was the True Author of the Shakespeare Plays,” (from the New York Times, 1916), https://sirbacon.org/links/nytimes.html

“Bacon’s Royal Parentage” (references prepared by Francis Carr). https://sirbacon.org/parentage.htm

“Baptismal Registration of Francis Bacon from St. Martin-in-the-Fields.” https://sirbacon.orgbaptismalregistration.htm

“The Bibliographies.” https://sirbacon.org/francis-bacon-the-bibliographies/

Biddulf, L., “Lord Bacon and the Theatre.” From Baconiana no. 108, July. https://sirbacon.org/links/lord_bacon_&_the_theatre.htm

“Binder’s Waste Discovery of a Manuscript Similar to Shakespeare,” Sotheby’s, July 21, 1992. https://sirbacon.org/graphics/sothebys.jpg

Bormann, Edwin, appendix to ch. 1, “Did Mr. James Spedding Really Know Everything about Francis Bacon?” from Francis Bacon’s Crytpic Rhymes

and the Truth They Reveal (1906), pp. 217-226 (“Bormann Spedding”). https://sirbacon.org/bormanonspedding.htm

Bridgewater, Howard (Barrister). “Evidence Connecting Sir Francis Bacon with Shakespeare.” The Bacon Society, London. https://sirbacon.org/ResearchMaterial/evidence.htm

Carr, Francis, “The Writer’s Finger Prints.” https://sirbacon.org/links/carrlegalquixote.html

Cockburn, N.B. [Nigel], table of contents, The Bacon Shakespeare Question, The Baconian Theory Made Sane (1998, reprinted 2024, The Francis Bacon Society Edition). https://sirbacon.org/cockburn.htm. Read excerpt: ch. 4, “Bacon’s Reasons for Anonymity” (pp. 40 – 54) https://sirbacon.org/anonymous.htm. Reviewed by Mather Walker, https://sirbacon.org/mcockburnreview.htm [and later by the present writer, https://sirbacon.org/downloads/Cockburn%20review%20sirbacon%205-3-23.pdf].

Cooper, D. W. and Gerald, Lawrence. “A Bond for all the Ages: Sir Francis Bacon and John Dee: The Original 007.” https://sirbacon.org/links/dblohseven.html

“Directory of Sir Thomas More, Document Unravelled,” by Edwin J. Des Moineaux. https://sirbacon.org/stmcontents.htm

Dodd, Alfred, “Francis Bacon and his Nemesis Edward Coke.” https://sirbacon.org/cokeandbacon.htm

— “The Sublime Prince of the Royal Secret,” from The Marriage of Elizabeth Tudor, pp. 38-42. https://sirbacon.org/doddsublimeprince.htm

Gentry, R. J. W., “Francis Bacon and the Stage” (from Baconiana). https://sirbacon.org/links/bacon&_the_stage.htm

Johnson, Edward D., a chapter from “Francis Bacon’s Promus,” The Shaksper Illusion. https://sirbacon.org/links/notebook.html

Lawrence, Sir Edward Durning, “Francis Bacon and the English Language.” https://sirbacon.org/links/BaconEnglishLanguage.htm

Leith, Alicia Amy, “Bacon on the Stage.” From Baconiana, July 1909. pp. 150 – 162. https://sirbacon.org/leithbaconstage.htm

“Manes Verulamiani (Shades of Verulam),” transcribed by Willard Parker (1927). pdf. https://sirbacon.org/Parker/Parker_ManesVerulamiani.pdf (“Showing contemporary opinion of Francis Bacon as Author, Statesman, Upright Judge, Philosopher and POET”)

Pares, Martin, “Parallelisms and the Promus,” https://sirbacon.org/mp.html. From Baconiana, August 1963.

“Maureen Ward Gandy,” https://sirbacon.org/links/gandy.htm [ee also Maureen Ward-Gandy, report, “Elizabethan Era Writing Comparison for Identication of Common Authorship,” 1992, reviewed for Lawrence Gerald, 1994, with professional credentials update, pdf, https://sirbacon.org/elizabeth-era-writing-comparison-for-identification-of-common-authorship/ (first published in Francis Bacon’s Hidden Hand (New York: Algora Publishing, 2018)

“The Northumberland Manuscript, Bacon and Shakespeare Manuscripts in one Portfolio!” https://sirbacon.org/links/northumberland.html.

“Northumberland Manuscript Parts I and II,” Collotype and Fascimile of an Elizabethan Manuscript, Preserved at Alnwick Castle, Northumberland, transcribed and edited with notes and introduction by Frank L. Burgoyne. librarian of the Lambeth Public Libraries. London: Longmans, Green, 1904. pdfs. https://sirbacon.org/ResearchMaterial/nm-contents.htm

Patton, Kenneth R. Setting the Record Straight, bk 1, The Vindication of William Stone Booth. https://sirbacon.org/pattonstrs.htm

Purchase, Heather, “Writing’s on the Wall for Shakespeare” (London Evening Standard, July 30, 1991). https://sirbacon.org/links/handwriting1.html

Schoch, Juan, “The Private Manuscript Library of Francis Bacon” (“cokeandbacon”). https://sirbacon.org/Tottel.htm

Von Kunow, Amelie Deventer, Francis Bacon, the Last of the Tudors, transl. Willard Parker, President, Bacon Society of America (1924). Electronically typed and edited by Juan Schoch. https://sirbacon.org/vonkunow.html

Wheeler, Harvey, “Francis Bacon’s Case of the Post-Nati (1608)” (From Wheeler’s CV: “The Case of the Post-Nati; Baconian Foundations of Constitutionalism,” (2000) under submission (paper delivered at Univ. of London symposium, Sept, 1999.). https://www.sirbacon.org/wheelerpostnati.html. [See also “Selected Works – Harvey Wheeler,” The Constitution Society, orig. 7/10/1997, last updated 3/24/21. https://constitution.org/2-Authors/hwheeler/hwheeler.htm; Wheeler CV, https://constitution.org/2-Authors/hwheeler/cv_short.htm]

** *

The article “Shakespeare Authorship Question” (undated), http://shakespeareauthorshipquestion.org/ (https not available), says it is “Wikipedia-based” and conforms to “Wikipedia policies and guidelines as they pertain to alternative theory and minority view articles.” It is not specific to the Baconian theory, but does name and contain links to main Baconian websites SirBacon.org (although it does not give the current link for the Francis Bacon Society. When next updated, perhaps it could be expanded to include additional candidates and resources, now that collaboration among playwrights has become more accepted, based on stylistic evidence. Its bibliography could be expanded to include recent books by Barry R. Clarke (2019), Peter Dawkins (the latest are 2004, 2020), N. B. Cockburn (2024 reprint), Brian McClinton (2008), and myself (2018) to its bibliography.

“Sir Francis Bacon, Baron Verulam, Viscount St. Alban, 1561-1626,” Shakespearean Authorship Trust (undated), https://shakespeareanauthorshiptrust.org/bacon.

William H. Young, “Modern vs Western Thought: The Return of Bacon’s Idols,” Dec. 21, 2017, https://www.nas.org/blogs/article/modern_vs._western_thought_the_return_of_bacons_idols. “In its rejection of reason, logic, and rationality and turn to thinking based on feeling and subjectivism, Modern thought suffers many of the biases and disorders of human nature in reaching conclusions that Sir Francis Bacon long ago called “idols.” In the Seventeenth Century, Bacon initiated not only the Scientific Method and Revolution, but the Western objective and philosophic worldview of man, nature, and, the secular state …. This article summarizes Bacon’s “idols” and compares them to the disorders and biases in some contemporary examples of Modern thought.”

Courses on Bacon

Dr. Joshua Sipper. Video. “Sir Francis Bacon’s Novum Organum: Overview and the Four Idols.” Study.com. https://study.com/academy/lesson/novum-organum-by-sir-francis-bacon-summary-analysis.html.

Caveats

There seem to be a lot of listings in this category. Sometimes, when it comes to Francis Bacon, it seems as if the voice of the truth will always be muffled by biased propaganda which does not stand up to critical analysis. Researchers are urged to take the time and trouble to verify statements presented as facts.

Philip K. Hall, “In defense of the Upstart Crow,” Ars Notoria, Humane Socialism (6 Feb. 2022), last accessed 7-11-25), https://arsnotoria.com/2022/02/06/in-defence-of-the-upstart-crow/ This is an opinion piece in which the author erroneously states that Francis Bacon’s piece, “The Interpretation of Nature,” from the Novum Organum, is a poem. It is not a poem. It is a work of prose. It is unfair to compare a work of prose to a poem as Hall does. Several poetry websites online also wrongly call “The Interpretation of Nature” a poem. https://hellopoetry.com/poem/66613/the-interpretation-of-nature/, https://www.poemhunter.com/poem/the-interpretation-of-nature-and/ and https://poetandpoem.com/Sir-Francis-Bacon/The-Interpretation-of-Nature-and. Hall claimed Bacon writes like an academic rather than a poet; however, the poet Percy Bysshe Shelly acknowledged that “Lord Bacon was a poet.” Even Bacon’s works of philosophy are full of metaphors. As a general observation, Bacon tends to be more fairly treated in writings where opinions are backed up with facts. Did Bacon write poetry? Yes. Did he write a letter to a friend, John Davies, asking him to be “good to concealed poets?” Yes. (See my blogpost, “So Desiring You to be Good to Concealed Poets,” Aug. 27, 2025, this website. On references to Bacon as a poet, see my paper, “Reports of the Death of the Case for Francis Bacon’s Authorship of Shakespeare Have Been Greatly Exaggerated,” SirBacon.org, August 3, 2022, pp. 8-11, https://sirbacon.org/reports-of-the-death-of-the-case-for-francis-bacons-authorship-of-shakespeare-have-been-greatly-exaggerated/).

Britannica. Peter Michael Urbach and Kathleen Marguerite Lea (with Anthony M. Quinton and Baron Quinton’s names listed at the bottom). “Francis Bacon: British Author, Philosopher, and Statesman.” Now undated, last accessed 10-2-25. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Francis-Bacon-Viscount-Saint-Alban. They have made some of the changes I suggested when I first wrote to them. Unfortunately, negative editorial bias against Bacon still mars their article. For example, it still says Bacon was “cold-hearted, cringed to the powerful, and took bribes, and then had the impudence to say he had not been influenced by them” (under “Legacy and Influence”). To the contrary, I would refer readers to Nieves Matthews, Francis Bacon: The History of a Character Assassination (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992) which the article does now cite. There was previously, I believe, an incomplete listing of Bacon’s legal works which has been removed altogether. On Bacon as a lawyer and judge, see Daniel R. Coquillette’s book, Francis Bacon, Jurists: Profiles in Legal Theory (Stanford: Stanford University Press: 1992). Bacon was a true Renaissance man. As James Shapiro observed in Contested Will (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2010), the only kind of writing he did not try his hand at was play-writing (p. 90).

There is no mention of the word “Shakespeare” in this article, although it is mentioned in the (unfairly disparaging) article on Delia Salter Bacon, the first person to propose reading Shakespeare as literature. And yet, the Britannica‘s article, “Edward de Vere, 17th earl of Oxford: English poet and dramatist” (currently undated), presents a case for Oxford as Shakespeare! What does it mean to state that Oxford became, in the 20th century the “strongest candidate proposed” for Shakespeare authorship? Who decides? The article says, “Evidence exists that Oxford was known during his lifetime to have written some plays, though there are no known examples extant.” Then what is the evidence? Where is independent evaluation or referral to sources evaluating the pros and cons of Oxford as Shakespeare? The Shakespeare plays are full of law. Was the Earl of Oxford a lawyer? Well, no, though he was admitted to Gray’s Inn. It is discussed in Alan Nelson’s book, Monstrous Adversary, which explains why the Earl of Oxford makes an unlikely Shakespeare? Oxford wrote poetry, but it the Oxfordians have taken the most notice of it. Bacon wrote fine court masques of which examples survive, and, in his biographer Spedding’s opinion, Bacon had the “fine phrensy of a poet,” using Shakespeare’s phrase. Was that a hint?

In my opinion, the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy‘s article on Bacon is a more objective article for a discussion of Bacon’s philosophy, although it disappointingly links to David Simpson’s biased IEP article, to be discussed. One would have to hope that the editors of the Encyclopedia Britannica were not taking sides in the Shakespeare Authorship debate.

Heitman, Danny. “Francis Bacon, Montaigne’s Rival,” Humanities. Spring 2022, vol 43, no 2, https://www.neh.gov/article/francis-bacon-montaignes-rival. (I moved my review to https://christinagwaldman.com/2023/08/22/review-of-danny-heitman-francis-bacon-montaignes-rival-humanities-spring-2022-vol-43-no-2/).

Articles targeting young readers

“Francis Bacon,” Britannica Kids (undated but copyright 2025), https://kids.britannica.com/students/article/Francis-Bacon/273048. Perhaps in response to my Sept. 15, 2024 email to Britannica Kids, the accuracy of this article has been improved. It now correctly says that Francis Bacon was the second son of Sir Nicholas and his second wife Anne Cooke, not his second son, period (Nicholas Bacon had three sons and three daughters with his first wife, Jane Fearnly; see https://luminarium.org/encyclopedia/nicholasbacon.htm). The correct publication date of Bacon’s science fiction novel, New Atlantis, is now given (1626, not 1610).” The article currently says Bacon began his career in the House of Commons in the “early 1580’s.” Bacon entered Parliament in 1581, not 1584, according to https://historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1604-1629/member/bacon-sir-francis-1561-1626). They have taken out any reference to the term “reader.” The term has evolved since it was used in the 16th century at the Inns of Court. Then, a Reader gave a reading. If he gave a second reading, he was called a Double Reader. Francis Bacon had given two readings on The Statute of Uses, so he was a Double Reader. Nowadays, of course, the term refers to a lecturer at a British institution of higher learning. (See Francis Bacon’s Hidden Hand, p. 110. As to Bacon’s Novum Organum (Latin for “new tool or method”), as the book–published under the title Francisci de Verulamio, summi Angliae cancellarij instauratio magna (1620)–is called. It was a complete book. However, by the term instauratio magna, Bacon envisioned a six-part project which he never completed. Instauratio Magna is translated: “great renewal.” I would say, it would be like a return of a golden age (of learning). See Coquillette, Francis Bacon, 77-78, 81, 90-91, 2-3, 293. This can be confusing. Here’s a page on “this book” from the Milestones of Science Books website, https://www.milestone-books.de/pages/books/002277/francis-bacon/instauratio-magna-novum-organum?soldItem=true. The Novum Organum is considered part 2, but it was published before part 1, the de Augmentis (1623) which was, however, an expanded Latin version of book 2 of The Advancement of Learning, in English (1605). This article on Bacon’s “Great Instauration” by the Francis Bacon Research Trust may be helpful: https://www.fbrt.org.uk/hermes/great-instauration/.

“Francis Bacon: Facts for Kids,” Safe Wikipedia for Kids,” last edited 9-2025. https://wiki.kidzsearch.com/wiki/Francis_Bacon: They have improved the article by removing inaccurate content. As to how long Bacon was in the Tower, the above article says: “for a while.” Yet, the very source they footnote, Luminarium, says, “He was sentenced to a fine of £40,000, remitted by the king, to be committed to the Tower during the king’s pleasure (which was that he should be released in a few days), and to be incapable of holding office or sitting in parliament.” He was only in the Tower four days, and his $50,000 fine was remitted. There is strong evidence that Bacon was the victim of a political plot engineered by his enemies which would defect attention from the King’s own scandals. Read Nieves Matthews, Francis Bacon,The History of a Character Assassination; James Spedding, Evenings With a Reviewer, 2 vols (London, 1881); Alfred Dodd, The Martyrdom of Francis Bacon (New York: Rider, 1946) (reviewed by me: “Review: The Martyrdom of Francis Bacon, by Alfred Dodd,” SirBacon.org, August 24, 2021, https://sirbacon.org/christina-g-waldman-reviews-alfred-dodds-book-the-martyrdom-of-francis-bacon/); “Was Bacon Guilty of Bribery or was he Politically Framed?” Excerpts from Edward Johnson, ‘Francis Bacon versus Lord MacAulay,'” https://sirbacon.org/baconbriberyreview.htm. I have written to the editors at https://www.kidzsearch.com/contactus.html on Sept. 15, 2024. One has a right to expect scrupulous attention to factual accuracy in an article for children.

“Francis Bacon,” Academic Kids (undated). Children doing reports for school will probably be drawn to such articles, but this one does not seem to have been written for children. Yes, Francis was the “youngest of five sons of Sir Nicholas Bacon,” but he was the second son by Nicholas’s second wife, Anne Cook. Sir Nicholas also had daughters–a fact worth mentioning in today’s enlightened times? Sir Nicholas was a Protestant, but not a Puritan; there is a difference. William Rawley, Bacon’s chaplain, in his Life of Bacon, said Bacon was born at “York House or York Place.” There is documented evidence (not just biographers believe, as the article states) that Bacon was tutored at home in his early years by his mother, a learned Latin and Greek scholar who had translated from Latin into English an important Protestant work, John Jewel’s Apology for the Church of England (1562, translation 1564), and then by John Walsall (see, e.g., Brian Vickers, intro. to his Francis Bacon: The Major Works (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), p. 35). The article states: “To support himself, he [Bacon] took up his residence in law at Gray’s Inn in 1579.” To clarify, in 1579, he was just beginning his study of law at Gray’s Inn. The History of Parliament website says Bacon’s first representation in Parliament was in 1581, not 1584. Bacon would not be admitted to the bar as an utter barrister, able to practice law, until 1582. Bacon entered Cambridge at age twelve, not thirteen. Without support, the article states that Bacon first met the Queen when he was thirteen when the Queen visited him at Cambridge. To the contrary, there are reports that the Queen visited the home of Nicholas and Anne Bacon at Gorhambury several times when Francis was growing up. Sir Nicholas was the Queen’s Lord Keeper. (See “Francis, The Queen, and Leicester,” https://sirbacon.org/francisqueenleicester.htm. Also: “When Francis was about 5 years old the Queen asked him his age. He answered with much discretion, being but a Boy, that he was two years younger than Her Majesty’s happy Reign: with which answer the Queen was much taken.” (“Chronology Related to Francis Bacon’s Life, https://sirbacon.org/links/chronos.html). Another source says the Queen herself gave him an examination in Latin before judging him qualified to begin attending Cambridge University, at age twelve. That is interesting, but no primary source is provided (See “The Rise and Fall of Sir Francis Bacon, Lord Chancellor and Viscount St. Albans,” History Picture Archive, Look and Learn, no. 323 (first pub. 3-23-68, posted online 7-10-13), https://www.lookandlearn.com/blog/25664/the-rise-and-fall-of-sir-francis-bacon-lord-chancellor-and-viscount-st-albans/ (last accessed 10-2-25).

***

Wikipedia

We expect an encyclopedia article to meet certain standards, that it will provide sufficiently complete, objective, unbiased, and factually accurate content. Do Wikipedia articles meet those criteria? Granted, some Wikipedia articles are probably more reliable than others. However, on biographies, Wikipedia has fallen short in the past. It has been sued because of its defamatory biographies of living persons. On a subject as controversial as Shakespeare authorship, there is every reason to read critically, for editors are only human, and we must all strive to be objective. I urge authors/editors of encyclopedia articles to check every fact in several reputable sources and strive to keep personal or official bias and propaganda out of the writing.

- “Francis Bacon,” last edited 25 August, 2025 (British style), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_Bacon. The article focuses on Bacon as philosopher and statesman. The article says Bacon produced “The Masque of Flowers” (citing Christine Adams, ‘Francis Bacon’s Wedding Gift of A Garden of a Glorious and Strange Beauty for the Earl and Countess of Somerset’, Garden History, 36:1 (Spring 2008), p. 45). However, Bacon wrote at least six masques which were performed at Gray’s Inn and at court. The article subjectively says, “To console him for these disappointments …,” Essex gave Bacon Twickenham Park (under “Final Years of the Queen’s Reign,” fn 31, “Bunten, Alice Chambers. Twickenham Park and Old Richmond Palace and Francis Bacon: Lord Verulam’s Connection with The, 1580–1608. R. Banks. p. 19.” This book was published in 1912. You will see it says nothing about “console.” You can read it for yourself at HathiTrust, https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/011590102.). The word “console” makes Bacon sound like a wounded child, suggesting unjustified bias. For Bacon, having an official position meant having a livelihood, a necessary means to economic survival. Perhaps this gift of land from Essex was intended in part as compensation for professional services Bacon had already rendered to Essex.

- (cont’d) To be clear, Bacon began his Gray’s Inn study of law in 1579. Daniel R. Coquillette’s Francis Bacon, Jurists: Profiles in Legal Theory (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1992) is an important source on Bacon and law. It deserves better than to be relegated to footnote 103 (formerly 101) where it is still one of three sources given for a single quotation not on law at all. On Bacon’s law reforms, see ch 2, pp. 70-76. Sadly, the Wikipedia states that “few of Bacon’s proposed law reforms were adopted during his lifetime,” citing a 1961 article in New Scientist (“Francis Bacon,” Wikipedia, fn 113)! The editors should read Coquillette’s book. Bacon instigated the hiring of court reporters, instead of the judges reporting their own. He is largely responsible for the passage of important new insurance legislation in England, the Francis Bacon Act. “There is some contemporary evidence that” he is responsible for the equity of redemption in foreclosure law; at least, that “the change in practice occurred during his Chancellorship (1617-1621).” See J. H. Baker, An Introduction to English Legal History, 3d ed. (London: Butterworths, 1990), pp. 127; 355-356, at 356 n 88. His work on Slade’s Case was important in the development of modern contract law; on Slade’s Case, see Baker, pp. 54, 161, 227, 388, 392-393, 395-397, 407-408, 415, 416, 420, 450. In Francis Bacon’s Hidden Hand (FBHH), I wrote, “One of Bacon’s practical reforms was the “confession of judgment,” an efficiency measure which Lord Coke, finding it “too novel,” would not allow” in a 1613 case (FBHH, p. 48). In The Merchant of Venice, Antonio says, “Let me have judgment and the Jew his will.” Merchant, IV, 1, 84 (1864 Globe ed., OpensourceShakespeare.com). “There is evidence that it was during Bacon’s Chancellorship that legal title began to pass to a mortgagor.” (p. 49). As Prof. Coquillette wrote, Bacon’s description of what a law report should entail is still considered valuable today (Coquillette, Francis Bacon, p. 253). An important resource is Barbara Shapiro, “Francis Bacon and the Mid-Seventeenth Century Movement for Law Reform,” The American Journal of Legal History 24, no 4 (Oct. 1980), pp. 331-362, at 353. For “Francis Bacon, Reformer” in FBHH, see pp. 47-49.

- The Wikipedia article, “Masque,” as of 22 August, 2025 (British style), mentions Bacon once, stating only that he paid for “The Masque of Flowers” (citing only Martin Butler, The Stuart Court Masque and Political Culture (Cambridge, 2008), pp. 8, 77, 214; see: “Masque,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Masque). Bacon was an important contriver of masques. See Bacon’s essay, “Of Masques and Triumphs”; Peter Dawkins, “Baconian Poetry,” Francis Bacon Research Trust (“FBRT”), https://www.fbrt.org.uk/shakespeare/baconian-poetry/ (poetry and masques); Brian Vickers, intro., in Vickers, Francis Bacon: The Major Works (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002 [1996], xxiv-xxx.

- “Shakespeare authorship question,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shakespeare_authorship_question, as of 27 August, 2025 (British style). This article clearly favors the Stratfordian theory of Shakespeare authorship. It presents the case for Bacon in the past tense when it is still very much alive. It links to a separate Wikipedia article, “Baconian Theory of Shakespeare Authorship.” Harold Love’s suggestion that Shakespeare picked up all the law he needed from drinking with lawyers is ludicrous (fn 129). The article does not reference modern Baconian resources (listed below).

- Granted, some improvements have been made in the article since I first started “Bacon on the Web.” The bibliography now includes an external link to the Shakespeare Authorship Coalition, providing an indirect reference, at least, to Shakespeare Beyond Doubt? Exposing an Industry in Denial, ed. John M. Shahan and Alexander Waugh (2016; first published by Tamarac FL: Llumina Press, 2013), the Coalition’s response to Paul Edmondson and Stanley Wells’ Shakespeare Beyond Doubt: Evidence, Argument, Controversy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013). Mentions of David Kathman and Terry Ross’s out-of-date “Shakespeare Authorship Page” (“last retrieved Dec. 17, 2010”) have increased from six to seven. Now, instead of incorrectly stating that (St. Louis) judge Nathaniel Holmes, author The Authorship of Shakespeare, 2 vols (New York: Hurd & Houghton, 1866), was a Kentucky judge, the article simply leaves out the fact that he was a judge at all. Previously, the article erroneously stated Bacon wrote no poetry at all. Now it incorrectly states “His only attributed verse consists of seven metrical psalters, following Sternhold and Hopkins,” citing “Halliday, 1957”[238]. That is not true. He wrote the poem, “The Life of Man,” and he tells us he wrote a sonnet for Queen Elizabeth. His biographer and editor James Spedding wrote that Bacon possessed the “fine phrenzy of a poet,” using Shakespeare’s phrase. The poet Shelley recognized Bacon as a poet (See Percy Bysshe Shelley, A Defense of Poetry (1821), p. 10; Yasmin Solomonescu, “Percy Shelley’s Revolutionary Periods,” ELH 83, no 4 (2016), 1105-1133, 1105-06, 1108 (quoting Shelley’s letter to John and Maria Gisbourne, 10 July 1818, in The Letters of Percy Bysshe Shelley, 2 vol., ed. Frederick L. Jones, Oxford: Clarendon Press (1964), 12:20, JSTOR, 26173906. He wrote in a letter to his friend John Davies, “So desiring you to be good to concealed poets ….”

- “Baconian theory of Shakespeare authorship,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baconian_theory_of_Shakespeare_authorship, as of 10 August, 2025 (British style). Tom Reedy, a member of the Oxfraud Facebook page, contributed to the editing on May 28, 2023. Oxfraud’s Twitter profile claims its goal is to stamp out all opposition to its core belief that William Shaxpere of Stratford wrote the Shakespeare works. (We see Reedy editing Shakespeare authorship here as well, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Talk%3AShakespeare_authorship_question%2FArchive_30, as of Oct. 5, 2021, accessed 8-28-24 and 2-15-25). Shakespeare’s plays are mentioned but not his sonnets. The article is slanted against the Baconian theory. The reference section includes links to the Francis Bacon Society (but it is not a recent link; it is a link to the Wayback Machine that says “coming soon”! What more needs to be said?) and SirBacon.org, but not to the Francis Bacon Research Trust. It leaves out modern authors Brian McClinton, Peter Dawkins, N. B. Cockburn, Barry R. Clarke, and myself, let alone older writers which one can find in the extensive SirBacon bibliographies. It was good, however, to see lawyer Penn Leary’s book, The Second Cryptographic Shakespeare (1990), listed (read it for free at SirBacon.org). It does, at least, mention Bacon in connection with masques. It calls Bacon’s Promus a “waste book” (an account book in bookkeeping) instead of a “commonplace book,” which it is. In fact, under the Wikipedia article, “Commonplace Books,” Bacon’s Promus is given as an example of a “commonplace book” (one in which an author or public speaker might jot down things he wished to remember, in an organized fashion, to use in his writing). Suggested alternative: “Sir Francis Bacon, Baron Verulam, Viscount St. Alban, 1561-1626,” Shakespearean Authorship Trust (undated), https://shakespeareanauthorshiptrust.org/bacon.

- “Francis Bacon Bibliography,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_Bacon_bibliography, last edited 19 July 2025 (British style). Some dates given are publication dates, but some are dates when composed, such as the “Gray’s Inn Christmas Revels,” for which Bacon wrote speeches for some of the speakers, which were not published until 1688. See https://www.graysinn.org.uk/latest-library-display-a-comedy-of-errors-and-revels-at-grays-inn/. I do not see that any changes were made from when it was “last edited.”

- “Author: Francis Bacon,” https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Author:Francis_Bacon, last edited 9 August 2025 (British style). It does not cite to modern editions. Not much effort was put into compiling this list.

- “Works by Francis Bacon,” ” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Works_by_Francis_Bacon, last updated 7 June 2025 (British style). For some reason, there are two bibliographies: this one, “Works by Francis Bacon,” (an “overview”) and the aforementioned “Francis Bacon Bibliography.” Under “Bibliography” on this page, they list Benjamin Farrington’s book, The Philosophy of Francis Bacon (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1964) which contains translations. The Wikipedia editors must not have ever looked at the book. It contains a bibliography, but none of the books in that bibliography are by Bacon himself.

***

David Simpson, “Francis Bacon,” Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, https://iep.utm.edu/francis-bacon/. Undated, last accessed Nov. 10, 2024. Discussed at “Bibliography–Commentary,” this website, https://christinagwaldman.com/bibliography-baconshakespeare-commentary/. As he does in his Oxford Bibliographies online entry on “Francis Bacon – Philosopher,” (“last reviewed Oct. 17, 2022),” he cites the unreliable historian (without mentioning Nieves Matthews, Francis Bacon: The History of a Character Assassination [New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996] MacAulay as if he were an authoritative critic on Bacon (claiming MacAulay “borrow[ed] a phrase from Bacon’s own letters” in calling him “a most dishonest man.” Simpson opines, without explanation, that it was a “virtual certainty” that Bacon was not Shakespeare. “Virtual” is an interesting word, as one of its meanings is “being in essence or effect, but not in fact.” In emails responding to mine to him, he denied that he took sides, but rather, cited “both his avid defenders and his staunch critics (yes, including Macaulay).” He stated that his overall opinion of Bacon was “highly favorable” (David Simpson to me, Oct. 28, 2020). In an earlier email to me, in response to my statement that, “I write as a courtesy to let you know that I do take issue with your stating it is a “virtual certainty” that Francis Bacon did not contribute to the authorship or editing of the works of Shakespeare. https://christinagwaldman.com/selected-bibliography-a-work-in-progress/,” he responded: “You’ve distorted my claim. I said that “it’s a virtual certainty that Bacon did not write the works traditionally attributed to William Shakespeare.” I said nothing about whether Bacon may have edited, revised, added to, or in some other way contributed to those works. If you have evidence that he did, then by all means publish it. And if your arguments and evidence are able to convince the scholarly community, then that is good for you and good for Lord Bacon. At that point, I’ll be happy to revise my statement. For now, I’ll let it stand.” (David Simpson to me, Oct. 14, 2020). On Macaulay, Brian Vickers wrote that MacAulay’s “notorious essay in the Edinburgh Review for July 1837 had a considerable influence, with its sarcastic distortions of both Bacon’s life and philosophy, but its failings are now generally appreciated (although Spedding’s masterly Evenings with a Reviewer … is not as well known as it should be) ….” (Brian Vickers, Francis Bacon and Renaissance Prose (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1968), p. 256, 256-257, 259, 305; Nieves Matthews, Francis Bacon: The History of a Character Assassination (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996), pp. 17, 19-33, et al.

—-

Dubious attempts by feminists and others, led by Carolyn Merchant beginning with her book, The Death of Nature, first published in 1982, to discredit Bacon by uncritically, negatively associating him with the “domination of nature” are prevalent. Are young scientists being uncritically taught Merchant’s openly-expressed dislike of Bacon? As just two examples, see David Fideler, “Restoring the Soul of the World,” 2013, https://www.thesouloftheworld.com/the-new-experiment-putting-nature-on-the-rack/ and https://www.sarthaks.com/664067/how-do-carolyn-merchant-and-francis-bacon-differ-in-their-views. See, e.g., my essay, “Francis Bacon, Shakespeare, and the ‘Secrets of Nature’: Violence, Violins, and–One-Day–Vindication?” pdf, May 21, 2021); Jill Line, “Following the Footsteps of Nature,” 1995, 6/2020, Francis Bacon Research Trust (under Resources), https://www.fbrt.org.uk/essays/. Here is Paul Krause, “The Death of Ecofeminism,” Crisis Magazine, Jan. 24, 2023, https://www.crisismagazine.com/opinion/the-death-cult-of-eco-feminism?mc_cid=67d6710298 (does not mention Bacon whom the eco-feminists have blamed for problems in the modern world due to scientific progress).

1-8-25: “Francis Bacon” (1561-1625), Geniuses, undated, https://geniuses.club/genius/francis-bacon. The article contains inaccuracies. This sort of article which does not document its source material or give an author’s name often does, in my experience and opinion. Bacon met Queen Elizabeth before he went to Cambridge as a young scholar at age twelve; Bacon began his studies of law, not his practice of law, in 1579 at Gray’s Inn. Et cetera. How would they know what his I.Q. was?

Stanford Global Shakespeare Encyclopedia (“SGSE”)

For some time, this website does not seem to have been available to the general public. A search for it brought up various “colloquys.” https://shc.stanford.edu/search?search=stanford%20global%20shakespeare%20encyclopedia&f%5B0%5D=site_section%3A141. On Jan. 20, 2023, I made the following observations before the site became unavailable to me. Prior to that time, although the site had articles up on Francis Bacon and the Bacon Shakespeare Question, it did not yet have a finished introduction on its “About Us” page. Yet, it already included seventy-one articles by David Kathman, an independent scholar who wrote the pro-Stratfordian article on Shakespeare authorship concerns for The Cambridge Guide to the Worlds of Shakespeare, vol 1 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019) (in which he erroneously wrote that Francis Bacon left no books or manuscripts in his Will). He was, until recently, listed as a member of Oxfraud (Oxfraud.com and Oxfraud Facebook group), a “Stratfordian” group which has stated in its Twitter profile that it has a goal of stamping out opposition to its core belief that William Shaxpere of Stratford was Shakespeare, rather than that Shakespeare was a pseudonym. Their name would lead one to believe that their main focus for antipathy is Edward de Vere, the 17th Earl of Oxford. As Brian Vickers has observed, many people do not have a particular knowledge of Francis Bacon’s life or works. Before people rule out Bacon as author, should they not spend some time learning more about him and his works, keeping an open mind? This link contains a description of the SGSE website’s conception, in 2018 by Haiyan Lee of Stanford on the Ohio State University website: https://u.osu.edu/mclc/2018/05/07/stanford-global-shakespeare-encyclopedia/. This is all I know at the moment.

David Colclough, “Bacon, Francis.” One might wonder why Bacon is given an entry in a Shakespeare encyclopedia if the topic of Bacon’s authorship of Shakespeare is not going to be addressed in the article (Well, they did add a brief reference to Bacon’s mentioning a Shakespeare play during his participation in Essex’s trial.). Bacon’s years in France are usually given as 1576-1579 (the article says 1575-76). How was Bacon a “client” of Buckingham’s? Rather, my impression is that the elder statesman Bacon tried to guide and improve the young, corrupt “favorite” of King James. For his troubles, he was “rewarded” by becoming the scapegoat of James and Buckingham in his politically-motivated removal from office as Lord Chancellor in 1621. But Bacon did not languish in self-pity. No, he made the last years of his life productive, in terms of his writing and publication.

David Kathman, “Authorship Question.” The treatment, including the “Further Reading” section, seems underdeveloped and one-sided, as of 2/8/23. Let us see if these articles have been revisited when the SGSE comes out of development. As of 2/8/23, Further Reading” contained no books newer than James Shapiro’s 2010 book, Contested Will (New York: Simon and Schuster, reprinted in 2017 without change). Kathman actually refers to his and Terry Ross’s “Shakespeare Authorship Page” online which does not appear to have been updated in some time.

David Kathman, “Baconian Theory,” https://shakespeare-encyclopedia-stage.stanford.edu/entry/baconian-theory. Why is “William Shakspere of Stratford” not also treated as a theory, albeit one which has come to be accepted without much further inquiry by many? The scientific method we are taught in grade school teaches us that any theory may be revisited when new evidence comes to light. The “Further Reading” section here still contains only two books, one by H. N. Gibson (1962) and one by John Michell (1996). British barrister N. B. Cockburn’s book, The Bacon Shakespeare Question: The Baconian Theory Made Sane (now reprinted in The Francis Bacon Society Edition, 2004), strives, and succeeds, I think, in presenting the authorship question and the Baconian “theory” in an extremely objective and fair-minded light.

David Kathman, “Northumberland Manuscript,” https://shakespeare-encyclopedia.stanford.edu/entry/northumberland-manuscript. The entire article is still only six lines long. There is a see also to the “authorship question.” There is no mention of Bacon’s essay, “Of Tribute, or, giving that which is due” (see Brian Vickers, ed. Francis Bacon: The Greatest Works (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002, p.b.), “Note on the Text” front matter; 22-51), a copy of which was first found in the Northumberland Manuscript. There is no “further reading” section. Not a single reference is mentioned for “Baconian” sources on the Northumberland Manuscript, such as those collected at SirBacon.org, including: a recent paper and video by “A. Phoenix,” Nov. and Dec., 2022, available from https://sirbacon.org/a-phoenix/; “The NorthumberlandManuscript,” https://sirbacon.org/links/northumberland.html; https://sirbacon.org/NMANUSCR.HTM; and Peter Dawkins, “The Northumberland Manuscript,” Francis Bacon Research Trust, https://www.fbrt.org.uk/essays/. For more resources, do a search in the search bar on the home page of SirBacon.org. It should be remembered that even “Stratfordian” Shakespeare scholar James Shapiro in his 2010 book Contested Will referred readers on the Baconian question to two resources in particular: Brian McClinton, The Shakespeare Conspiracies: A 400-Year Web of Myth and Deceit and SirBacon.org which collects many resources in one place, including Baconiana, the journal of the Francis Bacon Society, digital and indexed. Kathman was, and still may be, a member of the Oxfraud group on Facebook (associated with Oxfraud.com) whose purpose seems to be to quash nonconforming opinions in as harsh and belittling a way as possible, without open-minded consideration (For the record, I have never been a member of their Facebook group, although I have posted there with information on Francis Bacon.). Kathman was wrong in saying Bacon bequeathed no books or manuscripts in his Will, in his chapter in the Cambridge Worlds of Shakespeare (To read Bacon’s Will, see James Spedding, et al, The Works of Francis Bacon …, 14 vols. (London, Longmans ed., 1857-1874), 14: 539-546, 539 (2d sentence of 2d par.), 540, 541, 542. It can be read at HathiTrust.org.) Those who know Shakespeare well may not necessarily know Bacon or his writings well; for people do not read Bacon’s writings as they did in past times, as Brian Vickers has observed. Vickers is the author of Francis Bacon: The Major Works and many studies on Bacon and Shakespeare; he is a former chair of the Oxford Francis Bacon Project.

***

10-11-22: This entry is now a blogpost, “The Oxfraudian “Prima Facie Case” for Shakespeare: ‘Hoist with its Own Petard’?”

Shakespeare Authorship Roundtable (“SAR”) page on Bacon

11-19-22, revised 11-10-24. The SAR has made some changes I suggested, after which they told me not to contact them again. Perhaps the SAR initially relied upon “Francis Bacon, Biography” at GreatThinkers.org, https://thegreatthinkers.org/bacon/biography/ to which they refer readers. The SAR article says Bacon was “awarded a law degree at Gray’s Inn in 1582.” However, the Inns of Court were not identical to modern law schools. They did not award law degrees. In 1582, Bacon was admitted to practice as an utter barrister when the older, more experienced members of the Inn deemed him ready. It was a mentoring system. He had begun his studies at Gray’s Inn in 1579. The Biography.com article on Francis Bacon to which the SAR article refers readers also gets this wrong. Bacon was exceptional. Normally, one was an “inner barrister” for seven years before one was ready to become an “utter barrister.” Bacon was made Bencher at Gray’s Inn in 1586. He was the first to become a Bencher without having first been a Reader. He became a Reader in 1588 with his first reading on the Statute of Uses, followed by a second reading in 1600 when no one else wanted to give one, thus making him a “double Reader.” However, being a “Reader” at Gray’s Inn was not the same thing as being a “Reader” or lecturer at a British college today. The term has evolved. It meant he had given a “Reading,” which was a special event held during a school vacation. See chapter six, “A Law Professor by Any Other Name,” in my book, FBHH, pp. 109-111 and sources cited therein, including J. H. Baker and Margaret McGlynn, as well as “Francis Bacon,” Gray’s Inn, https://www.graysinn.org.uk/the-inn/history/members/biographies/francis-bacon/; Daniel R. Coquillette, “Chronology of Bacon’s Career,” Francis Bacon (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1992), appendix 1; and Brian Vickers, ed., “Principle Events in Bacon’s Life,” The History of the Reign of Henry the Seventh (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), xxxvi. The SAR article erroneously states that Bacon began his career as a member of Parliament in 1584; however, it appears he began in 1581, according to “Bacon, Francis (1561-1626),” History of Parliament, https://historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1558-1603/member/bacon-francis-1561-1626 (first paragraph under “Biography”). The article states that he traveled extensively in Europe. The only source for this of which I am aware is Pierre Amboise’s biography (see “Resources,” below and Peter Dawkins’ essay, “The Bacon Brothers and Italy,” https://www.fbrt.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Bacon_Brothers_and_Italy.pdf. He did not just “serve on Queen Elizabeth and King James’ councils”; he held a special position as Counsellor Extraordinaire under both rulers. Queen Elizabeth had created the position just for him. It was an unpaid position under Queen Elizabeth; a paid one under James. The Roundtable article states that The Advancement of Learning and New Atlantis were Bacon’s “best known” works (source?). That might be debatable. Gutenberg.org ranks Bacon’s Essays, Wisdom of the Ancients, and New Atlantis as his most popular works. I would not call the Northumberland Manuscript “22 sheets of notes.” See A Phoenix, “The Northumberland Manuscript” (Nov. 2022), SirBacon.org, https://sirbacon.org/downloads/aphoenix/NORTHUMBERLAND%20MANUSCRIPT.pdf

For further reading, the SAR article links to the Biography.com (Heart Digital Media, last updated Aug. 9, 2023) article on Bacon, but that article has its own problems. Bacon’s new scientific method was in contrast to Aristotle’s, not a continuation of it, and Bacon did not study Aristotle at Gray’s Inn, but at Cambridge. “The Great Saturation?” They must mean the Great Instauration, Magna Instauratio. New Atlantis was not published until 1627, posthumously, along with the Sylva Sylvarum, both unfinished; Apophthegmes was first in 1625, reprinted 1626. Come on, people! I am looking at Daniel R. Coquillette, Francis Bacon, appendix II, “Chronology of Bacon’s Most Important Philosophical and Juristic Writing,” which uses Spedding’s Works of Francis Bacon (London: Longmans, 1857-74) and R.W. Gibson, Francis Bacon: A Bibliography of his Works … (Oxford, 1950). It is not that difficult to get things right if one takes care. The site says, please contact us if you see errors. I have done so and, alas, have received no response.

The Oxfraud.com page on Francis Bacon as Shakespeare

11-19-22 (updated 9-2-25): : The Oxfraud.com page on Francis Bacon, “Mmmm! Bacon!” is a cleverly written opinion flawed by omissions and factual inaccuracies (You will find it under “Categories,” “Better Candidates,” undated, https://oxfraud.com/index.php/BC-Bacon). It does not cite sources. It leaves out the important biographical information that Bacon, after several years as a student at Cambridge University, spent three years “in France,” studying “with a civilian” (one trained in the Roman, civil law) and serving in Queen Elizabeth’s diplomatic service from 1576-1579, only then returning to study law at Gray’s Inn after his father, Sir Nicholas Bacon,’s death. In France, Bacon was involved with the Pleiade, a group of French classical poets led by Pierre de Ronsard. Brian Vickers wrote that Bacon’s years in France had not been adequately studied. I have pointed the problems with this page out to the “Oxfraudians” in a discussion on their Oxfraud group Facebook page on 2/28/22, but they have not made changes. The comments date from 2013, which is some indication of the date of the article.

- The article paints Bacon’s life story in an unfairly negative light, ignoring contrary evidence, such as Nieves Matthews’ 1998 book, Francis Bacon: The History of a Character Assassination (Yale University Press). It does not take the arguments in favor of Bacon’s contribution to Shakespeare authorship seriously; in fact, it does not really discuss them at all, instead focusing on Delia Bacon’s failures (of note, she was probably the first to suggest reading the Shakespeare plays as literature in her 1857 book), Mark Twain (who was no slouch in the intellectual department, writing Is Shakespeare Dead? (1909)), and ciphers (depicting Dr. Orville Owen’s cipher wheel). However, the evidence in favor of Bacon’s authorship of Shakespeare goes far beyond Delia, ciphers, or even Twain’s arguments.

- The information on the Oxfraud.com Bacon page in question is largely based on opinions insufficiently supported (in my opinion) by facts. Nor does it cite to sources telling where those interested in hearing both sides of the argument can learn more, as James Shapiro, although a professed “Stratfordian,” does in his book, Contested Will: Who Wrote Shakespeare? which was reprinted, without change, despite valid criticisms of it, in 2017 (first published by Simon & Schuster in 2010). For further reading on Bacon and Shakespeare authorship, Shapiro directs readers to the website, “Francis Bacon’s New Advancement of Learning,” https://sirbacon.org/ and Brian McClinton’s book, The Shakespeare Conspiracies: Untangling a 400-Year Web of Myth and Deceit, 2d ed. (Belfast: Shanway Press, 2008). McClinton states in his book that he is endeavoring to continue the work begun by N. B. Cockburn, author of the 740-page The Bacon Shakespeare Question: The Baconian Theory Made Sane (London: The Francis Bacon Society Edition, 2024 [1998]).

- For example, the article says, “The problem was, there really is not much to link Bacon with Shakespeare except the view that Shakespeare just had to be a brilliant scholar. Their writings are nothing alike, the range of knowledge Shakespeare displays is but a few grains of sand in the beach of Bacon’s learning so that if Bacon was writing as Shakespeare he was deliberately dumbing down, and Bacon was, well, far to busy with other things to bother writing Shakespeare.” Yet, the Oxfrauds give no examples. What works of Bacon’s have they actually read? They reject evidence to the contrary, such as Bacon’s Promus and the many other parallelisms that researchers have unearthed between Bacon’s works and those attributed to Shakespeare. Of course, one writing a play will employ a different style than one writing essays, or imaginative dialogue, or futuristic novel, or masque, or book of philosophy–all of which Bacon did write. Stratfordians have to dumb down the extent of Shakespeare’s learning, for there is little more than speculation that Shakspere of Stratford ever attended even the Stratford grammar school. That is demeaning to the Shakespeare works, as Brian McClinton discusses in his book, The Shakespeare Conspiracies. “What is happening now is that the works themselves are being reduced in meaning and significance in an attempt to make them cohere with the mundane and mercenary life of William of Stratford.” (p. 12).

- In sum, the Oxfraud.com Bacon page in question treats a great and good man disrespectfully. It does not take the argument for Bacon’s contribution to Shakespeare seriously, but rather, presents it as a defunct joke. It does not address UK forensic handwriting expert Maureen Ward-Gandy’s 1992 Report, “Elizabethan Era Writing Comparison for Identification of ‘Common Authorship,'” first published in my book, Francis Bacon’s Hidden Hand New York: Algora Publishing, 2018), appendix 4 (pp. 247-274), now online at What’s New, SirBacon.org, Oct. 11, 2022, https://sirbacon.org/whats-new-on-sirbacon-org/.

Some Resources

Francis Bacon is so often worth quoting: “It is hard to remember all, ungrateful to pass by any.”

Clarke, Barry R. Francis Bacon’s Contribution to Shakespeare: A New Attribution Method (New York: Routledge, 2019) (arguing for a collaborative approach and finding stylistic evidence of Bacon’s involvement)

Cockburn, N. B. The Bacon Shakespeare Question: The Baconian Theory Made Sane. The Francis Bacon Edition (1998; reprinted by The Francis Bacon Society, 2024). Presenting decades of original research by Cockburn, an Inner Temple barrister, whose stated goals are to present the “points that matter,” present a comprehensive case, and introduce readers to “one of the most remarkable and fascinating intellects in our history” [pp. 6 – 7].

Dawkins, Peter. On Second-Seeing Shakespeare. e-book, 2020. Peter Dawkins, https://www.peterdawkins.com/publications/ (informative, available on Kindle, my review accessible here)

—The Shakespeare Enigma, foreword by Mark Rylance (London: Polair Publishing, 2004). For a complete list of Peter’s publications and videos, see the Francis Bacon Research Trust “Resources” tab.

Crowell, Samuel [pseud., former college instructor]. William Forty-Hands: Disintegration and Reinvention of the Shakespeare Canon. Charleston WV: Nine-Banded Books, 2016. Explains why the single-author theory is passe.

Matthews, Nieves. Francis Bacon: The History of a Character Assassination. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996. Essential in countering the myth that Bacon was a “cruel, corrupt, and power-hungry politician” (bookjacket).

McClinton, Brian. The Shakespeare Conspiracies: Untangling a 400-Year Web of Myth and Deceit, 2d ed. Belfast: Shanway Press, 2008. First pub. 2007 by Aubane Historical Society. My review may be accessed here).

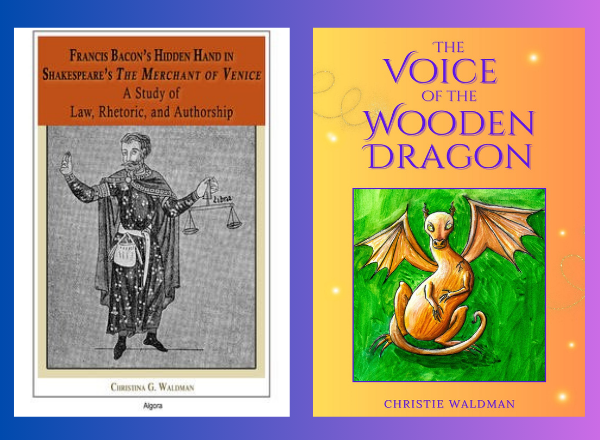

Waldman, Christina G. Waldman. Francis Bacon’s Hidden Hand in Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice: A Study of Law, Rhetoric, and Authorship. New York: Algora Publishing, 2018 (exploring the connection Mark Edwin Andrews, writing in 1935, first observed between Francis Bacon and Bellario [the old Italian jurist who is usually overlooked in productions] in The Merchant of Venice–in his book, Law versus Equity in The Merchant of Venice: A Legalization of Act IV, Scene 1 [Boulder: University of Colorado Press, 1965). Additional bibliographies in progress, https://christinagwaldman.com/more-by-the-author/

Murtha, Ryan. Murtha, editor and intro, Innocent Gentillet, Anti-Machiavel: A Discourse Upon the Means of Well Governing, translated by Simon Patericke (1602) (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2018) (His introduction explores parallel passages in works by Bacon, Shakespeare, and other writers of seventeenth century literature for which authorship remains uncertain; see my review in Modern Language Review 115, no 3 (July, 2020)); also, The Precious Gem of Hidden Literature (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2022) (setting forth parallels with claims to first finding and publication).

Francis Bacon Research Trust. Peter Dawkins, founder and principal. https://www.fbrt.org.uk/. With bibliography.

Francis Bacon Society members have been researching and publishing their findings in their journal, Baconiana, since 1886, available from https://francisbaconsociety.co.uk/ and https://sirbacon.org/baconiana-collection/. The Francis Bacon Society also has a YouTube video channel with much good content, including videos by actor Jono Freeman (“JonoFreeman33,” https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCU6OOFE4_Jg3cl7EvOVGyyg, Peter Dawkins, and Simon M. Miles. See also their Bibliography and Bookstore sections.

SirBacon.org, https://sirbacon.org/francis-bacon. Over 1000 pages of content indexed by Google and extensive bibliographies.

Klein, Jurgen, editor, “Francis Bacon,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (“SEP“), with bibliography, https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/francis-bacon/.

Biographies of Bacon

- Jurgen Klein, “Francis Bacon,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, last revised 2012, https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/francis-bacon/ (although it unfortunately links to Simpson’s IEP article.

- Peter Dawkins, “Baconian History,” “Life of Francis Bacon,” and other essays (under “Resources”), Francis Bacon Research Trust (“FBRT”), https://www.fbrt.org.uk/

- Rawley, William (Bacon’s chaplain), Life of Bacon (Spedding 1:1-20), reprinted at Francis Bacon Research Trust, https://www.fbrt.org.uk › wp-content › uploads › 2020 › 06 › Rawleys_Life_of_Francis_Bacon.pdf.

- Amboise, Pierre Amboise, “Discourse on the Life of M. Francis Bacon, Chancellor of England,” Histoire Naturelle de Mre. Francois Bacon, Baron de Verulan (sic), Vicomte de Sainct Alban et Chancelier d’Angleterre (Paris, 1631), reprinted at https://sirbacon.org/amboiselife.htm (text provided by Mather Walker, linking to text of Granville C. Cunningham, ch 2, Bacon’s Secret Disclosed in Contemporary Books (London: Gay & Hancock, 1911).

Last updated 10-2-25