June 1, 2025.

It is often said or implied, by analogy with the principle that possession is nine tenths of the law, that the burden of proof is on the heretics to dethrone Shakspere if they can. This is a misconception. A “burden of proof” is an artificial concept which has no place in human thought unless it is necessary for practical reasons. In a law suit, for example, where the Court must give judgment one way or the other, the law imposes a burden of proof on one party to prevent stalemate if the evidence seems equally balanced. But in an academic dispute such as the authorship controversy one must simply weigh the evidence for each side, imposing an equal burden on each, and then deliver one of three alternative verdicts: (1) that the evidence seems equally balanced, in which case neither side can be declared the winner; (2) that one side, named, is probably right; (3) that one side, named, is right beyond reasonable doubt.

N. B. Cockburn, The Bacon Shakespeare Question: The Baconian Theory Made Sane (1998, reprinted by The Francis Bacon Society in London, 2024), p. 6

Several years ago, I told Mark Johnson, an administrator of the “Oxfraud” group Facebook page, that when I had time, I would provide a written evaluation of their self-styled “Prima Facie Case (PFC)” (without conceding that they have one) for the proposition that William Shaxpere/Shakespeare of Stratford was the true author of the Shakespeare works, as is traditionally assumed (presented at https://oxfraud.com/sites/PrimaFacie.html).

Using a legal analogy, the “Oxfraudians” (“Stratfordians” who reject the claim that Edward de Vere, the 17th Earl of Oxford (1550-1604), was the true Shakespeare) have claimed their statement of the case was so strong that it entitled them to a presumption–a favorable legal stance–which would put the burden on their opponents to rebut their proof. Under modern rules of civil procedure (New York, for example): if the rebuttal was insufficient (as hypothetically decided by an impartial judge), they would win the case on the pleadings. If the rebuttal raised reasonable doubt, there would be a full trial on the evidence.

Going along with their analogy, I challenged whether they even had enough admissible evidence from which a (hypothetical) independent judge in a (hypothetical) court with jurisdiction could determine whether they had established a prima facie case justifying a presumption (“The Oxfordian Prima Facie Case for Shakespeare–Hoist With its Own Petard?” (last revised Oct. 19, 2024), https://christinagwaldman.com/2022/10/11/the-oxfraudian-prima-facie-case-for-shakespeare-hoist-with-its-own-petard/).

One reason why I have been reluctant to respond further to their PFC was that, under a legal analogy, the responder to a pleading is limited to responding to the points in the pleading. The PFC is too narrow; it excludes much of the case on either side. If some of the front matter to the First Folio is to be considered as evidence, then, arguably, all of the front matter to the First Folio should be considered. Notably, the PFC ignores the controversial point as to whether the Droeshout “portrait” was intended as a joke all along. What did Ben Jonson mean, in his poem facing the illustration, when he advised readers to “Look not on his picture, but on his book”? Take a look, for example, at Basil Brown (Isabelle Kittson Brown)’s entertaining short book, Supposed Caricature of the Droushout Portrait of Shakespeare [made by John Taylor, the “Water Poet”] (privately printed, 1911), pp. 26-28 (of 34), available at https://archive.org/details/supposedcaricatu00brow, and Baconian researcher A. Phoenix’s paper, “The Title Page and Droushout Mask of the 1623 First Folio …” (July 2023), also available at https://www.academia.edu/104366783/.

Hence, the second reason: I am not convinced the Oxfraudians are being entirely serious (in earnest). The PFC may be tongue-in-cheek, like the illustration on their website’s page for Bacon (under alternative candidates) that displays four strips of bacon and does not take pains to present the facts of Bacon’s life accurately. And, they are crafty: they have claimed that persons who sign the Shakespeare Authorship Coalition’s “Declaration of Reasonable Doubt” are conceding that the Stratfordians have a prima facie case. I signed that document, but I didn’t consider it to be a “legal” document. I doubt anyone else did, either.

For historical reference, in 2013, Cambridge University Press published Shakespeare Beyond Doubt: Evidence Against Controversy, edited by Stanley Wells and Paul Edmondson. In response, the Shakespeare Authorship Coalition published Shakespeare Beyond Doubt? Exposing an Industry in Denial, edited by John M. Shanan and Alexander Waugh (Tamarac, FL, Llumina Press, 2013, reprinted 2016). Part 2 (of 3) of the latter book is “Exposing an Industry in Denial: The Coalition responds to The Shakespeare Birthplace Trust’s ’60 Minutes with Shakespeare.'” In “Sixty Minutes with Shakespeare” (2011), sixty-one questions pertinent to Shakespeare (and by extension authorship) are asked and then answered very briefly (one minute each in a video), each by a different Orthodox Stratfordian “expert.”

Peter Dawkins, founder and principle of The Francis Bacon Research Trust and author of The Shakespeare Enigma (Polair Publishing, 2004) is listed among the “Organizations Endorsing the Rebuttals” (p. 153). Dawkins responds to Questions: #38 (on the memorial bust, pp. 195-96), #39 (on Ben Jonson, pp. 196-97), and #45 (“Is Francis Bacon plausible?”). However, for some reason, his seven-paragraph response to “Is Francis Bacon plausible?” is not presented in the book. Instead, a reference is given to “DoubtAboutWill.org/exposing.” That reference is no longer good, however. The material has been moved to https://doubtaboutwill.org/downloads, Item 6 (“… Authorship Doubters Respond to ‘Sixty Minutes with Shakespeare'”).

I would encourage readers to track down Dawkins’ cogent, well-reasoned response (p. 49) which demonstrates that Bacon’s authorship is, indeed, quite plausible. Unfortunately, this flaw of omission in Shakespeare Beyond Doubt? may have misled other writers who have relied on this book into underestimating the viability of the case for Bacon. Most of the book chapter authors are known to be “Oxfordians.” Even though the book addresses many of the points in the PFC, this neglect of the case for Bacon makes me reluctant to recommend the book.

The assumption is too often prematurely made that the case for Bacon is dead (as Twain joked about his own death). Also, development of the case requires digging, and that digging requires skills and knowledge of foreign languages many no longer possess. The reward is in the digging, as Bacon observed, as paraphrased by Edwin Reed: “A father, dying, called his sons to his bedside and told them he had buried a treasure in his vineyard for them. In due time they found it; not in gold or silver, but in the bountiful crops that reward the spade and pick.” (Edwin Reed, intro., Francis Bacon: Our Shakespeare (Cambridge, MS, University Press, 1902), p. 1. As (“Stratfordian”) scholar Brian Vickers, who has studied both Bacon and Shakespeare, once wrote, “Francis Bacon is exciting!”

Why would Bacon have hidden his authorship? Conceivably, there are a number of plausible reasons that might come to mind–not to the exclusion of others: so he could speak freely about matters which might be considered treasonous, because he had enemies, some of whom were jealous of his tremendous intellectual abilities. This is my own opinion; I do not represent any other person or group. It is not my intent here to present the entire argument for/against Bacon’s “contribution to Shakespeare,” as Barry Clarke put it in the title to his 2019 book, listed in references at the end of this blogpost. That cannot be done in a brief blogpost.

It is true, one can take Shakespeare authorship too seriously, four hundred years after the fact, and it can be good to laugh at ourselves for doing so. Compared to the senseless killing of one nation’s people by another nation’s people which we hear about in the news daily, it seems inconsequential indeed. But the truth should always matter, and we should insist on standards in deciding what is factually true or not. Bacon helped to set those standards. Should not the true author(s) of the works be given proper credit? Is that not the morally correct thing to do? Have we not been put on notice by the paucity of Shaxpere’s biography that further inquiry is warranted?

This brief blogpost cannot possibly hope to present the entire case against Shaxpere’s authorship in any meaningful way; however, perhaps even a brief response may be helpful. It is true that, in my book, Francis Bacon’s Hidden Hand, I did not devote much space to the case against Shaxpere–as if he were “King of the Hill” which needed to be toppled before I could in good faith proceed to pursue an alternative theory. Beliefs based on what one has been taught can be very powerful, as can illusions. When I was writing my book, I had not yet heard of Brian McClinton’s book, The Shakespeare Conspiracies: Untangling a 400-Year Web of Myth and Deceit, 2d ed. (Belfast: Shanway Press, 2008) or I would have referred readers to it (in FBHH’s bibliography, see “Shakespeare Authorship Argued,” pp. 290-293). My position was–and is–that: whoever it was who wrote the works of Shakespeare, he had to have been a lawyer; and, since there was no proof Shaxpere was a lawyer, I felt free to explore my evidence in favor of an author who was not “just a lawyer” but eminently qualified in other ways as well: Francis Bacon. I did urge readers to find that I had presented a preponderance of evidence–enough to win in a civil court–that Bacon wrote The Merchant of Venice . (A preponderance of evidence is just enough to tip the scales–just a feather’s weight. See FBHH, p. 218.)

In my view, the Oxfraudian PFC lacks the kind of evidence, the quality of evidence, sufficient to prove a prima facie case. First, there are no manuscripts in Shaxpere’s handwriting. Granted, manuscripts were often not kept by printers after they printed them. However, in Shaxpere’s case, we do not even know what his handwriting looked like, because the six signatures are such poor samples, and there is no other writing of his to compare it to. See “Shakespeare’s Handwriting: Hand D in the Booke of Sir Thomas More,” last updated July 13, 2020, https://shakespearedocumented.folger.edu/resource/document/shakespeares-handwriting-hand-d-booke-sir-thomas-more.

Would one not think some sort of writing in his own hand–even a receipt–would have survived? But none has. Shaxpere mentioned no books or papers in his Will. In contrast, Bacon’s writings, including correspondence, filled fourteen volumes in the standard Longmans edition, The Works of Francis Bacon, edited by James Spedding et al (1857-74).

In fact, we even a Shakespeare (analog) manuscript in Francis Bacon’s own handwriting, a play fragment analog to the “Tapster” scene in The First Part of Henry the IV which was found in binder’s waste inside a 1586 Latin-Greek copy of Homer’s Odyssey (Geneva), in 1988. This was the conclusion of Maureen Ward-Gandy in her 1992 forensic report, “Elizabethan Era Writing Comparison for Identification of Common Authorship,” made for British historian Francis Carr, which was first published in my book, Francis Bacon’s Hidden Hand (appendix 4, “Handwriting on the Wall”) and in this blog (“Shakespeare Play Fragment – Said to be in Francis Bacon’s Handwriting,” revised Sept. 25, 2020, https://christinagwaldman.com/2020/05/14/fragment-of-i-henry-iv-found-in-binders-waste/. You can also read Ward-Gandy’s report here: “Elizabethan Era Writing Comparison for Identification of Common Authorship,” posted Oct. 11, 2022, https://sirbacon.org/elizabeth-era-writing-comparison-for-identification-of-common-authorship/.

What little we know about the biography of Shaxpere is simply not commensurate with his being the author of the Shakespeare works (plays and sonnets). We are told that he could have obtained a grammar school education in Stratford and either learned everything else he knew on his own or by asking others for information. However, as E.M. Dutton wrote in her e-book, Homeless Shakespeare, even to be admitted to such a grammar school, one had to be able to read English and Latin. So, that adds another layer to the speculation (Homeless Shakespeare: His Fabricated Life from Cradle to Grave, uploaded April 6, 2012, p. 30 (epub), Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/HomelessShakespeareHisFabricatedLifeFromCradleToGrave_991).

The Law in Shakespeare Tips the Scale: As I have said, it was after reading Mark Edwin Andrews’ 1965 book, Law versus Equity in The Merchant of Venice: A Legalization of Act IV, Scene 1 (Boulder: University of Colorado, 1965), that I became convinced that, whoever Shakespeare was, he had to have been a lawyer (see “Home page,” this website; ch 1, Francis Bacon’s Hidden Hand). In contrast, there is no evidence William Shaxpere of Stratford ever studied law at one of the Inns of Court; nor is there evidence–only speculation–that he ever clerked in a law office or asked his (assumed) friends at the Inns of Court questions in order to gain legal knowledge.

As for the “Oxfordian” candidate, Edward de Vere, American lawyer Thomas Regnier (d. 2020) states–without citation–that de Vere “studied law from an early age with his tutor, Sir Thomas Smith.” After that, while there is evidence Oxford was admitted to Gray’s Inn, there is no further evidence he continued his legal studies–at Gray’s Inn or elsewhere–or that he further advanced in the legal profession.

In contrast, Bacon began his serious study at Gray’s Inn in 1579 (having been admitted to Gray’s Inn in 1576 but not attending then). By 1582, he was admitted to the bar as utter barrister. His career in Parliament as a statesman had already begun, in 1581. By 1586, he was a bencher of Gray’s Inn. He did his first reading in 1587; his second in 1600. His vision of revolutionizing education in all aspects (e.g., his 1605 The Advancement of Learning) included legal reform. He held positions as Solicitor-General (1612), Attorney-General (1613), Privy Counsellor to King James (1616), Lord Keeper of the Seal (1617), and Lord Chancellor (1618-21) (see Daniel R. Coquillette, Francis Bacon, appendix 1, “Chronology of Bacon’s Career (1561-1626),” (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1992). Surely, of all possible candidates, Bacon was the one most qualified to have written the law that is embedded within the Shakespeare plays. In fact, Regnier concedes that Bacon was a “greater legal mind than Oxford was likely to have been.” (Thomas Regnier, “The Law in Hamlet: Death, Property, and the Pursuit of Justice” (2011), reprinted in Shakespeare and the Law: How the Bard’s Legal Knowledge Affects the Authorship Question, edited by Roger Strittmatter (Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship, June 2022), pp. 231-51, at 231). In my opinion, Regnier too easily dismisses the case for Bacon’s authorship on the basis of style (see Thomas Regnier, “Could Shakespeare Think Like a Lawyer?” (2003), reprinted in Shakespeare and the Law, ed. Strittmatter, pp. 187-230, at 201-02). How well do the Oxfordians–and Oxfraudians–know the case for Bacon?

Let us now look at the nine points of the PFC:

Point 1, “Title Pages: William Shakespeare’s name is listed as author on the title page or dedications of numerous plays and poems published from 1593 (Venus and Adonis) onwards.” Response: the question is: do we take was was written as literal truth, or is there reason to doubt its literal truth and read between the lines? A name written on a title page does not conclusively prove the named individual is the author, particularly in an age where the use of pseudonyms was prevalent. As Erasmus wrote, “Nothing is easier than to place any name you want on the front of a book.” (quoted by Samuel Crowell (pseudonym), William Fortyhands: The Disintegration and Reinvention of the Shakespeare Canon (Charleston, WV: Nine-Banded Books, 2016), p. 258). In fact, it is undisputed that Shakespeare’s name was printed on title pages of plays known not to have been written by “the real Shakespeare.”

If what Heminge, Condell, and Ben Jonson said in the front matter of the First Folio is to be interpreted as literally true, we have a paradox; for the unvarnished factual biography of Shaxpere is simply not commensurate with his being Shakespeare. Why would they have “lied”? Well, perhaps Heminge, Condell, and Jonson truly believed that what they wrote was true, as Crowell suggests in William Fortyhands (p. 258), but that alone did not make their statements objectively true. As to the resolution of the paradox, I think it is more likely that, for a variety of possible good reasons (e.g., protection from censorship, multiple authorship), it was decided that publishing the plays under a pseudonym/allonym was preferable to publishing under the name(s) of the true author(s). Granted, the similarity of the proposed pseudonym “Shakespeare” to the name of a real person “Shaxpere” associated with the theatre (as player, shareholder) was a weird, serendipitious, coincidence, under a pseudonym/allonym theory. I mean no disrespect by calling the Stratford man “Shaxpere” and the real poet (whoever it may be) “Shakespeare”; “Shaxpere” was a legitimate spelling of the Stratford man’s name. Were Heminge and Condell qualified to edit the Shakespeare works? I do not think so.

Ben Jonson knew Bacon well. I would argue that, if anyone knew about Bacon “being” Shakespeare, it was Ben Jonson. See, e.g.: Ben Jonson and the 1623 Folio,” an excerpt from Bertram Theobald, Enter Francis Bacon, https://sirbacon.org/bertrambj1623folio.htm; “Ben Jonson,” 1573-1635,” https://sirbacon.org/links/jonson.html, Edward D. Johnson, “Francis Bacon and Ben Jonson,” https://sirbacon.org/jonsonbacon.htm, “Shakespeare,” Francis Bacon Research Trust (Peter Dawkins, founder and principle) (last revised 28/2/25), https://www.fbrt.org.uk/shakespeare/ and the essays listed at https://www.fbrt.org.uk/?s=ben+jonson. Granted, this is a topic worthy of more extensive treatment than I’m giving it here.

Point 2: “Sharer in Lord Chamberlain’s and King’s Men: Many of the plays were identified as having been performed by the Lord Chamberlain’s Men or the King’s Men. Contemporary records show that William Shakespeare was a sharer in these playing companies.” Response: while it seems true enough that Shaxpere of Stratford was a sharer, or shareholder, in “these playing companies.” that does not also prove that he wrote the plays.

Point 3: “Shakespeare’s relationship with his fellow sharers—Richard Burbage, John Heminges, Henry Condell, Augustine Phillips, and others, as well as fellow householder Cuthbert Burbage—is well documented.” Response: the PFC points to the fact that Shaxpere received red cloth along with the other players; thus, he was a player. That is fine, as far as it goes. However, that does not by extension mean he wrote the Shakespeare plays and poems. The PFC provides a link to the Folger site, “Contemporary accounts and critical responses to plays” (undated), https://shakespearedocumented.folger.edu/resource/playwright-actor-shareholder/contemporary-accounts-and-critical-responses-plays. At first, this page would seem daunting, as if it contained incontrovertible evidence. However, the assumption that every reference to “Shakespeare” the poet/playwright(s) is a reference to “Shaxpere” is not fairly justified by the evidence.

A paradox exists: the biography of Shaxpere is not commensurate with his being the revered author. There are unexplained discrepancies. For instance, why did no one mourn Shaxpere as a poet/playwright when he died in 1616? And, since he was dead, how was he able to revise the plays that were revised for the First Folio? How is it that eighteen new plays could be included that had never been printed before? Why did he not write a eulogy when Queen Elizabeth died? (Bacon did, although it was not published until after his death.) Why is there no record of Shaxpere’s ever meeting in person with King James? (as Claire Asquith pointed out in Shadowplay [New York: Public Affairs, 2005], p. 190). How was it that Shaxpere (a mere player) would address the Earl of Southhampton so intimately in his dedication of Venus and Adonis to the Earl which was published in 1593? Bacon knew Southampton personally; Shaxpere did not. Shaxpere was not even “gent.” in 1593.

Point 4: “Named in the Will of a Fellow Player: Shakespeare was named as a “fellow” of Phillips in Phillips’ will when he died in 1605, along with other members of the King’s Men company (left of the page, 5th line from the bottom).” Response: This evidence can do no more than show that Shaxpere was a member of the King’s Men acting company. It does not show he wrote the plays/poems of Shakespeare.

Point 5: “Fellow Player Named as Trustee: Heminges was a trustee for “William Shakespeare of Stratford Vpon Avon in the Countie of Warwick gentleman” in the purchase of London property. Heminges later transferred the property to Shakespeare’s daughter Susanna.” Response: Again, this does not prove Shaxpere wrote the plays/poems of Shakespeare. All it shows is that Heminge (1) knew Shaxpere through having business dealings with him and (2) Shaxpere became part-owner of the real property Blackfriars.

Point 6: “Left Money to Fellow Players in Will: Shakespeare left Heminges, Burbage and Condell money to buy mourning rings in his will.” Response: this evidence shows that Shaxpere knew Heminge, Burbage, and Condell well enough to leave them a bequest in his will; however, it does not show he wrote the plays/poems attributed to “William Shakespeare.”

Point 7: “Shakespeare gent: The playwright was entitled to be referred to as “Gent.” – “M.” – or “Mr.”, a title that would apply to an individual whose family was entitled to bear arms.” Response: That is fine, but it is irrelevant to authorship.

Point 8: “the ONLY shakespeare gent.: Only William Shakespeare of Stratford had that distinction during that time period—no other William Shakespeare qualified.” Response: Yes, the spelling in the draft is closer to “Shakespeare” than to “Shaxpere” (it starts out with two “S”es). However, the draft refers to him as a “player,” not a “playwright.” Nothing I have seen in these materials establishes that Shaxpere-Shakespeare was a playwright. Nor, in my opinion, do these additional documents from the Folger: https://shakespearedocumented.folger.edu/highlights/shakespeares-coat-arms and the British Library, https://blogs.bl.uk/english-and-drama/2016/07/shakespeare-gentleman-or-player.html.

Point 9: “a worthy fellow: Heminges and Condell state that the works in the First Folio were written “to keep the memory of so worthy a friend and fellow alive, as was our Shakespeare.” Response: As I wrote above at “Point 1″: perhaps Heminge, Condell, and Jonson truly believed that what they wrote was true,” but that did not necessarily make it true. I object to calling Shaxpere-Shakespeare a “playwright” without proof. Here are links to the Folios online: https://www.folger.edu/explore/shakespeare-in-print/first-folio/ to https://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/facsimile/book/SLNSW_F2/index.html.

The PFC concludes: “The evidence demonstrates that William Shakespeare of Stratford was the author of the works.: He was named on the title pages of works published during his lifetime; he was a gentleman, entitled to be referred to as “M.”, “Mr.” or “gent.”, all of which were applied to the author in print and other extant records; and he had a well-documented personal and business relationship with the King’s Men playing company (formerly the Lord Chamberlain’s Men), and particularly with John Heminges [sic] and Henry Condell, compilers of Shakespeare’s First Folio, who named Shakespeare their “friend and fellow.” For good measure, they give a reference to the Folger “Shakespeare Documented” exhibition with its “491 items (and counting) which document Shakespeare’s life—as a playwright, poet, landowner, and Stratford-upon-Avon resident and celebrity.”

Response: For every one of their nine points, I find the “Oxfraudians” have failed to establish a prima facie case justifying rebuttal. Are we supposed to scour everything in the Folger exhibit looking for proof more specific and probative than that which they have set forth here? Presumably they have put their best evidence forward in these nine points. Has the PFC demonstrated that Shaxpere was “a landowner”? Yes. “Resident and celebrity”? Perhaps. But “poet, playwright, and author of the plays and poems of Shakespeare”? I do not see it. I do not think they have established their prima facie case.

Now, you might say, she’s writing as an advocate, not as an impartial judge. You are free to consider the fact that I spent three years researching and writing a book that argues that Bacon’s hand could clearly be seen in The Merchant of Venice, and that I continue my research, as time permits. However, I don’t think it is that difficult to read the text, compare it with the claims being made about it, and see that the evidence in the PFC’s nine points does not prove what the Oxfraudians say it does. Perhaps the Oxfraudians would care to try again.

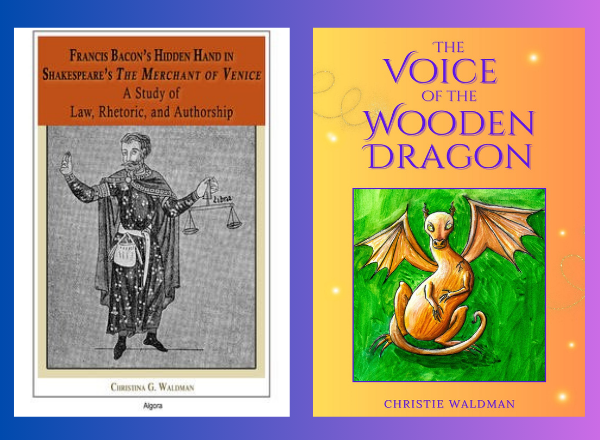

Readers are encouraged to investigate Shakespeare authorship further. To learn more about Bacon/Shakespeare, see the many resources at SirBacon.org, https://sirbacon.org/ (including the extensive writings and videos of the “A Phoenix” research team, https://sirbacon.org/a-phoenix/), the Francis Bacon Research Trust (Peter Dawkins, founder and principle), https://www.fbrt.org.uk/, and The Francis Bacon Society, https://francisbaconsociety.co.uk/. As for recent books, see Brian McClinton, The Shakespeare Conspiracies: Untangling a 400-year Web of Myth and Deceit, 2d ed. (Belfast: Shanway Press, 2008), Dr. Barry Clarke, Francis Bacon’s Contribution to Shakespeare: A New Attribution Method (New York: Routledge, 2019), N.B. Cockburn (British barrister), The Bacon Shakespeare Question: The Baconian Theory Made Sane (Francis Bacon Society Edition, 2024 [1998], and my own, Francis Bacon’s Hidden Hand: A Study of Law, Rhetoric, and Authorship (New York: Algora Publishing, 2018).

First posted May 30. Revised June 1, 2025. No AI scraping allowed. Limited quotation is allowed, so long as appropriate credit is given. This essay will also be posted to SirBacon.org. I am grateful to Lawrence Gerald for his helpful feedback.