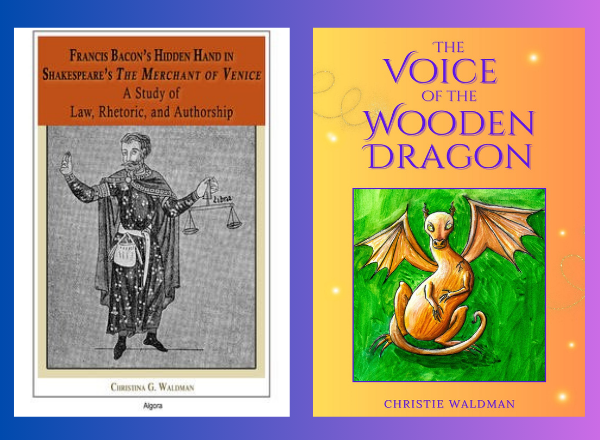

“Meet” my new book, The Voice of the Wooden Dragon! This one is for the kids. It has:

Dragons who do not fly.

A dragon princess whose plans go awry.

And a boy on a quest to find out why.

Things were not fair in Deweydaire, a land that was ruled by dragons. Humans worked while dragons played. Even though Princess Meredith was a dragon, she had taken the side of the humans. This did not endear her to her dragon relatives! She was willing to fight for the cause of human freedom, even when it meant going against her uncle, King Harold the Humble. But even she had her limits. How could she have known that things would go so wrong when her intentions were so noble? Somehow, with the help of her friends both dragon and human, she must defeat the power of an illegal magic spell, find her way home to Deweydaire, and reclaim all that she has lost. The story is co-authored by a disgruntled dragon who is a real stickler for accuracy. Get your copy from NFB Publishing, Bookshop, Amazon, and other sellers!

“Original, clever, and a fun read from start to finish. Especially and unreservedly recommended for … school … and community library Fantasy Fiction collections … ages 8-18.” –Children’s Bookwatch, Midwest Book Review

“A fantastic mix of fantasy fun, a bit of royal chaos, and a beautifully imagined world of dragons and humans … Very highly recommended.” –Asher Syed for Readers’ Favorite

Have you read Francis Bacon’s Hidden Hand in Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice:

A Study of Law, Rhetoric, and Authorship?

“This well-written book adds importantly to a long tradition. “Who wrote Shakespeare’s plays?” is one of the most persistent and nagging questions of all time. Some of us are so superficial that we incuriously would answer, “Why Shakespeare, of course.” But that’s not good enough for iconoclastic thinkers. Christina Waldman ably makes the case here for Shakespeare’s contemporary Francis Bacon as the author of The Merchant of Venice.” –Dan Kornstein, author of Kill All the Lawyers? Shakespeare’s Legal Appeal

“Francis Bacon’s Hidden Hand in Shakespeare’s ‘The Merchant of Venice’: A Study of Law, Rhetoric, and Authorship–a splendid and well researched book by Christina G. Waldman, J.D., an American lawyer. Available from Amazon.” –Peter Dawkins, Francis Bacon Research Trust (FBRT)

“The case for Francis Bacon’s authorship of Shakespeare’s works is undergoing a resurgence, having been eclipsed in recent years by other contenders. This is remiss, as there is plenty to discuss concerning Bacon’s possible hidden literary endeavours, especially in connection with that great legal satire, The Merchant of Venice, as Christina Waldman shows.” — Jerry Glover, review of Francis Bacon’s Hidden Hand, The Fortean Times, no. 378, April 2019, p. 65.

“….A thoroughly impressive work of iconoclastic scholarship, Francis Bacon’s Hidden Hand in Shakespeare’s ‘The Merchant of Venice’: A Study of Law, Rhetoric, and Authorship is a ‘must read’ contribution to the ever growing library of Shakespearian scholarship. As thoughtful and thought-provoking as it is meticulously researched and documented, Francis Bacon’s Hidden Hand in Shakespeare’s ‘The Merchant of Venice’: A Study of Law, Rhetoric, and Authorship is unreservedly recommended for personal, community, college, and university library Shakespearean Studies collections and supplemental studies reading lists.”– Julie Summers, Midwest Book Review, vol. 19, no. 6 (June, 2019).

You might wonder, “How could two books be more different?” This is true. However, they did come out of a common background, an interest in the Renaissance which began when I was an undergraduate at Southern Illinois University at Carbondale, Illinois, under the tutelage of Prof. Henry Vyverberg of the History Department, around 1980. I had wanted to choose Shakespeare authorship for an honors thesis topic. However, he encouraged me to choose something that “had not been done before.” So, I wrote about Castiglione and Machievelli’s perceptions of women, the “real” versus the “ideal,” instead. In researching that topic, I came across the strange Neoplatonist writers’ way of praising women, putting them on a pedestal, without affording them any real power. What a dangerous deception! The Voice of the Wooden Dragon explores the transformative power of art and the imagination, through the eyes of a female dragon who must learn to own her power. While The Voice of the Wooden Dragon is written to delight and entertain children and teens, there is “meat” to the story, even if the dragons of Deweydaire are vegetarians. I wrote the first draft in 1983. I did not get back to Shakespeare authorship for thirty-five years.

The book which inspired Francis Bacon’s Hidden Hand was Mark Edwin Andrews, Law versus Equity in ‘The Merchant of Venice,’ a Legalization of Act IV, Scene 1 (Boulder: University of Colorado, 1965). In a 1937 letter to Andrews, U. S. Supreme Court Justice Harlan F. Stone praised it: “Often, in listening to The Merchant of Venice, it has occurred to me that Shakespeare knew the essentials of the contemporary conflict between law and equity. But until I read your manuscript I had never realized how completely the play harmonized with recognized court procedure of the time. . . .You have done an admirable piece of work. . . . ” (ix, quoted by J. K. Emery, editor). This book has intrigued me ever since I happened across it in my college library around 1980. It convinced me that, whoever Shakespeare was, he had to have been a lawyer to have written the trial scene in The Merchant of Venice. In 2015, I finally sat down to write a short review of Andrews’ book for SirBacon.org, a wonderful website for doing research on Francis Bacon. That “short review” grew to book length, just as Andrews’ original two-week research project for a summer Shakespeare course turned into a book-length manuscript. Then it sat in storage for thirty years until a librarian rediscovered it, realized its merit, and arranged for its publication.

Andrews made two main points; briefly: one, that Shakespeare displayed significant legal knowledge, and two, that the play itself actually influenced the legal system. Although plainly stating he was a “Stratfordian” not a “Baconian,” Andrews could not help but observe that Francis Bacon played a real life role much the same as that played by Bellario in Merchant in a real-life court case, Glanvill v. Courtney (1616) in which Bacon advised King James. Thus, Andrews named Bacon as the amicus curiae in his own dramatization of Act IV, Scene 1.

So, who or what does Bellario represent? The literal meaning of this Italian name might be “beautiful song.” Perhaps, he represents a spirit of fairness and mercy which we might call “equity.” Bellario is the old Italian legal expert whom the Duke summons to advise him in the case. However, he is too old and sick to come to court, so he recommends Portia to appear in court in his stead. He provides her with his “notes” (short for “annotations”?) and the appropriate courtroom garb.

In my book, I explored Andrews’ second thesis: was Francis Bacon Bellario, or akin to Bellario? Researching this book felt like being on a treasure hunt, with each clue opening doors to the next. One of the things this play is about is the relationship between adornment and substrate, like a spice seasoning a dish by becoming a part of it, which is perhaps the way Shakespeare meant that mercy seasons justice or rhetorical flourishes strengthen an argument. One must get beyond superficial appearances to see all the levels of meaning that a superlative artist has put into a creation.

My research led me to Daniel R. Coquillette‘s book, Francis Bacon (Stanford University Press, 1992), “the first modern book to describe Francis Bacon’s jurisprudence,” and several of his articles on the influence of Roman (civilian or canon) law on Bacon and his contemporary English “common lawyers.” Richard Helmholz’s articles on the history of canon law introduced me to the twelfth century Italian jurists. The great Italian dottore Irnerius led a renaissance in legal education in twelfth-century Bologna, after a more complete text of the Code of Justinian was discovered, after four centuries. Italian canon law professor Andrea Padovani tells the story of Irnerius’s life and accomplishments in “Irnerius (ca 1055 to ca 1125)” in Law and the Christian Tradition In Italy, edited by Orazio Condorelli and Raphael Domingo (Routledge, 2020). His new book is L’insegnamento del diritto a Bologna nell’eta di Dante (“The Teaching of Law in Bologna in the Age of Dante.” Bologna: Societa Editrice Il Mulino, 2021). Who would have thought that tracing names in The Merchant of Venice would have led me to the twelfth century Italian jurists!

There is always something new to learn, in analyzing the names of people and places in the play. For example, Bellagio is a region in Lombardy, in Italy. Does “Bellario” hint at a famous jurist from Lombardy? “Bellario” is uncannily like the acrostic “FBLAWAO,” found in the opening lines of The Rape of Lucrece, as Mather Walker discusses in his 2000 essay, “The Symbolic AA, Secrets of the Shakespeare First Folio.” In those same lines, William Stone Booth found an acrostic of the name “Bacon” (Booth, Subtle Shining Secrecies Writ in the Margents of Books (Boston: Walter H. Baker Co., 1925), p. 55). Venice is famous for its bells, another apt association. Also, a bell is in the shape of a helmet, which suggests “Wilhelm” or “William,” as in the name “William Shakespeare”–so Peter Dawkins has observed in his new ebook, Second-Seeing Shakespeare: ‘Stay Passenger, why goest thou by so fast? (April 2020, available from FBRT). I believe the names in this play are particularly revealing, as I discuss in my book, chapters 8 and 9. Might Bellario even suggest Bellarmine?

In the past, some “orthodox” Shakespeare scholars made light of Andrews’ impressive accomplishment in writing his book on Merchant. B. J. and Mary Sokol actually accused their fellow scholar of “showing off” (“Shakespeare and the English Equity Jurisdiction, The Merchant of Venice and the Two Texts of King Lear,” The Review of English Studies, New Series, vol. 50, no. 200 [1999]). Harvard law professor John P. Dawson dismissed Andrews’ book as a “youthful escapade …. Though no new light is cast on Shakespeare, it must have been fun at the time.” (Shakespeare Quarterly 18, no. 1, Winter, 1967, pages 89–90, https://academic.oup.com/sq/article-abstract/18/1/89/5109434?redirectedFrom=fulltext). Justice Harlan Stone would not have concurred!

Why this harsh downplaying of Andrews’ significant contribution to Shakespeare scholarship? Is it because he suggested Bacon’s name in association with Shakespeare? Andrews spent his whole summer “turning o’er” old law books in the Guggenheim Library, much as Bellario says he and and “Balthazar” (Portia) had done (Andrews, Law v. Equity, xv, 85; The Merchant of Venice, IV, 1, 156 (1864 Globe ed., Open Source Shakespeare.) Scholars used to argue over whether Shakespeare actually knew any law, as O. Hood Phillips reported in Shakespeare and the Lawyers (London: Routledge, reprinted 2005 [1972]). However, it would seem that point has now been conceded. In his preamble to his book, Shakespeare and Law (London: Methuen Drama, 2010), Andrew Zurcher confidently stated the Shakespeare plays are full of law. However, I believe I am the first to look at Merchant in light of Bacon, the civil law, and Bellario. For pointing the way, I thank Mark Edwin Andrews and his book, Law versus Equity in ‘The Merchant of Venice. One never seems to be able to exhaust what can be said about any Shakespeare play, though. It is my sense that this play still holds many secrets.

You can read a sample of Francis Bacon’s Hidden Hand at SirBacon.org. I am grateful to Lawrence Gerald and Rob Fowler for posting earlier drafts of my book at SirBacon.org as “Bacon is Bellario With Just Deserts For All!” (July 28, 2016). (And thanks for the “Francis Bacon is Shakespeare” tee shirt, Lawrence!)

Francis Bacon’s Hidden Hand is available from Algora Publishing, the Francis Bacon Society Bookstore, Amazon, and other sellers.

Last updated May 4, 2025. First posted here Dec. 26, 2018.

Copyright 2018 – 2025 by Christina G. (Christie) Waldman. AI scraping is not permitted.

Dear Christina, of course, F. Bacon was an outstanding person. I read his `New Organon`, some treatises on history, as well as books about him, for example, Daphne du Maurier’s “Francis Bacon. His Rise and Fall” (all translated into Russian). But at the center of my interest is the Earl of Rutland, about whom much less is known, and he remains a mysterious person. I assume that the poetic fabric of Shakespeare’s plays (not the ideas) is Rutland’s doing.

Previously, his candidacy for the role of Shakespeare was defended by many authors, such as the Belgian Demblon, the American Bostelman, the Englishman Sykes. And now, apart from a few Russian-speaking researchers who were inspired by Gililov’s book, I don’t see anyone. Maybe you know such people?

I think I was able to contribute to Ben Jonson studies. So, in his comedy “Epicene” I guessed prototypes of almost all the characters. There Ben made fun of Rutland and Bacon (La Foole and Daw). All this is set out in my book –once again I will give you a link to it: [link removed, with apologies].

I’ll probably have to translate it into English somehow.

Dear Lev, if your book does get translated into English, please let us know. There is evidence of the contributions of a number of writers. [Added 12-28-2020: I watched Russian Professor Marina Litvinova in a July 9, 2012 interview on Prime Time Russia (YouTube video) say she changed her mind from believing Rutland was Shakespeare to becoming convinced it was Francis Bacon who wrote the histories, at least. At 6:08 minutes.] [Added 9-23-24: unfortunately, this YouTube video was no longer available for viewing in the U.S., by 7-21-22, so I am removing the link. But now, I sort of wish I had left it, even though it was expired, in case it ever becomes available for viewing in the U.S. again.]

Dear Christina, I received your post about Ruth Ginsburg yesterday and found your response to my comment — thank you. I`d like to clarify: Ilya Gililov developed the view of the authorship of the Earl of Rutland and his wife, and Marina Litvinova — Rutland and F. Bacon. It is her version that seems to me the most promising: it eliminates the disadvantages of Bacon (Bacon’s lack of great poetic talent) and of Rutland (too young to create historical plays).

I personally became interested in this problem after reading Gililov’s book (1997). I try to develop the Gililov-Litvinova approach. As a result of my research, I published a book (only in Russian) “Shakespeare: Faces and Masks” (2018, 228 p.). Available on paper and online. [link to site written in Russian language removed, with apologies]

As Litvinova showed (and I was able to confirm), the keys to many riddles should be found in the plays of Ben Jonson. He knew all the secrets and liked to use personal satire — to show on the stage his acquaintances. Litvinova argued that the main object of his satire was the Earl of Rutland. And I add: and F. Bacon. Some of the articles in my book are devoted to the analysis of several of Jonson’s plays. I also paid a lot of attention to the existing plaster mask, the picture “Chess Players”, etc.

By the way, do you know the hypothesis that “Don Quixote” was written by the same people who were behind the pseudonym “Shakespeare”? – see the book of the Briton Francis Carr `Who Wrote Don Quixote?` (2004).

Dear Lev, thank you for writing. I went to your website and read the parts that were in English. Regretably, I do not read Russian so cannot read your paper you have published there. I also see that Routledge has published vol. 18 of The Shakespeare International Yearbook with a special section on “Soviet Shakespeare,” edited by Tom Bishop and Alexa Alice Joubin (June 15, 2020). The abstracts are in English, so I presume the articles are as well. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/e/9781003048763.

“What is Truth, asked jesting Pilate, and would not stay for an answer.”–Francis Bacon. Francis Bacon was a poet, though. If readers have not read the 19th century German Edwin Bormann’s book, Francis Bacon’s Cryptic Rhymes, engagingly translated by Harry Brett, I heartily encourage them to do so. . As to Francis Carr’s book, Who Wrote Don Quixote?, readers will find the first chapter at the website, Francis Bacon’s New Advancement of Learning, http://www.SirBacon.org .

I have read Gililov’s book. He had come to the United States to study at the Folger Library. Though his book focused on the Rutlands, he did say he suspected that Bacon played a role as editor of a circle of writers. Such a vast literary project as the works called Shakespeare required a super-mind, the mind of the multi-faceted humanitarian genius Francis Bacon. True, there are many fascinating literary mysteries involved. The Earl of Rutland could be considered a young protege of Bacon’s.

I am grateful that the study for my book led me to read the writings of Francis Bacon in more depth. As has been said by Jonson, Rawley and others, as cited by Nieves Matthews in her book, Francis Bacon: The History of a Character Assassination (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996), those who knew well him loved him. And so I hope that everyone who is looking into the authorship question will read the writings of Francis Bacon. I hope that my book will help them do that. Readers can find the standard Longmans edition of James Spedding, Robert Leslie Ellis and Douglas Denon Heath,The Works of Francis Bacon, Baron of Verulam, Viscount St. Alban, and Lord High Chancellor of England, 14 vols (1857-74), as well as earlier editions such as Basil Montagu’s, which includes works Spedding left out, at the HathiTrust.org website. Many thanks for sharing your information, Lev. Eventually, we hope, all the true facts will come together one day to make up the complete picture.

I would like to add that the Russian scientist Professor Marina Litvinova wrote the book “Shakespeare’s justification”, published in 2008 in Moscow (600 pages). Unfortunately, the book is not translated into English. Its concept: Shakespeare = Roger Manners, 5th Earl of Rutland + Francis Bacon, tutor of this Earl.

Dear Lev, thank you for writing. I have read Russian scholar Prof. Ilya Gililov’s book, in translation: The Shakespeare Game: The Mystery of the Great Phoenix (New York: Algora Publishing, 2002). Like Litvinova, Gililov proposed that the Earl of Rutland, Roger Manners (1576 – 1612), and his wife Elizabeth wrote works attributed to “Shakespeare,” as part of a “Shakespeare Circle.” Gililov wrote that he suspected that Francis Bacon served as master editor to this group (On the “Shakespeare Circle,” see Peter Dawkins’ essay, “The Shakespeare Circle,” at the Francis Bacon Research Trust website (https://www.fbrt.org.uk), under “Resources, “Essays,” and Peter Dawkins’ paper, “The Shakespeare Circle,” read at the Globe Theatre Authorship Conference, July 2005, http://www.sirbacon.org/shakespearecircle.htm. Other proponents of Rutland as a “Shakespeare” author have included German literary critic Karl Bleibtrau (1907) and Russian exile P.S. Porohovshikov (1940)(See Les Hewitt, “The Shakespeare Authorship Question,” Historic Mysteries, Sept. 5, 2015, https://www.historicmysteries.com/william-shakespeare-authorship/). For those interested, Francis Bacon’s letter, “Advice to the Earl of Rutland on his Travels” is in James Spedding, ed., Works of Francis Bacon (London: Longmans, 1857-1874), vol. 9, pp. 6-15, HathiTrust, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/hvd.32044105219521.